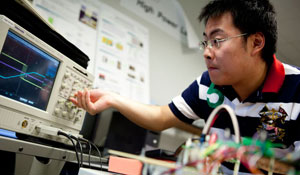

Xiaohu Zhou, a Ph.D. student in electrical engineering at North Carolina State University, is working on a power electronics converter for a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle charging station. A charging station allows electricity to flow in and out of the grid, making cars a source of electricity storage. (Photo by Eileen Mignoni)

At 5 p.m. after a long day’s work, you drive your plug-in electric car to your garage. The car’s battery is fairly full because you drove little today. You plug your car into a charging station, but rather than recharge, you de-charge, pumping excess energy back into the power grid system and helping meet peak energy demand.

“It’s like the Internet,” says Dr. Alex Huang, an electrical engineering professor at North Carolina State University, “but rather than share bits of information—such as Twitter messages and YouTube links—you share electrons.”

Sharing energy is just one use of what has been dubbed the Smart Grid, a leaner, more intelligent version of the existing grid. As envisioned, it would use information technology and two-way digital communications to increase grid productivity, diagnose and treat its own problems, and allow consumers to better manage their energy use.

Experts claim this technology will save money for both consumers and utilities and will reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Department of Energy, for example, estimates that increasing the grid’s efficiency by 5 percent would be the equivalent of removing 53 million cars from the road. But some observers note the high cost of equipment to operate a smart grid system could short-circuit the effort.

The way the grid stands now, utilities transmit power whenever a user flips a switch. Companies cannot monitor where the energy actually goes or where it is lost along the lines. During peak hours, companies meet demand by using backup “peaker plants,” such as coal-fired power plants, or by buying energy on the stock market. The expense eventually is passed to the consumer, and because the backup system generally relies on dirtier generation methods, it produces more carbon.

Homes with smart meters connected to the Smart Grid could help to reduce lost power and save money. For example, a consumer could program his or her air-conditioning system to raise the thermostat in warm weather when demand for air conditioning rises or prices are high.

The Smart Grid could also increase access to distributed generation, or on-site renewable energy sources. Huang envisions intelligent homes equipped with small-scale solar generation units that could feed a large battery located at the edge of town.

“When demand is high, it’s more economical to use energy stored in a battery rather than turn on a coal-fired power plant,” Huang says. In addition to his work at North Carolina State University, Huang directs the National Science Foundation’s FREEDM Systems Center, which is developing Smart Grid components capable of storing and distributing renewable energy.

These transitions will not happen overnight.

Gangyao Wang and Tiefu Zhao electrical engineering Ph.D. students, pass electrical waves through a silicon-based solid state transformer. Solid state transformers, currently in the first phase of development, will allow houses with personal alternative energy generators to feed energy back into the electrical grid. (Photo byEileen Mignoni.)

The Department of Energy would like to see a comprehensive national Smart Grid by 2030. In northern Kentucky and parts of Ohio, Duke Energy, the nation’s third largest electric utility, will install 700,000 electric smart meters and 450,000 natural gas smart meters during the next five to seven years. The installation will cover 84 percent of Duke Energy’s utility customers in these two states.

Developing this system is also costly. Although Duke Energy has allocated $1 billion for hardware installation in Ohio, Indiana and the Carolinas over five years, these funds “won’t build our entire service area,” says Paige Layne, the marketing communications manager for Smart Grid technology at Duke Energy.

The future cost to consumers will vary by state. In Ohio, for example, consumer rates increased 50 cents per month this year and will increase by $1.50 in 2010. But since customers will be better able to manage their consumption with Smart Grid technology, the bills will go down, says David Mohler, vice president and chief technology officer for Duke Energy. Last year, 35 participants in a pilot study in Cincinnati reduced their consumption by 10 to 20 percent.

The biggest challenge is battery technology, Mohler says. Vehicle batteries require a carrying capacity thousands of times that of a cell phone battery. Engineers have yet to develop one that is both cheap and reliable.

Still, pilot projects provide a glimpse of the future.

Xcel Energy aims to make Boulder, Colo., the first “smart” city by the end of 2009. And Duke Energy has already launched a self-healing grid in Hendersonville, N.C. When a tree fell on Duke Energy lines in June 2009, a nearby network station sensed and isolated the problem area. The station sent an automatic SOS to Duke Energy, quarantined the outage, and rerouted power to affected homes and businesses in a matter of seconds.

Without this intelligence, homeowners must report disruptions to the power company. Then a team of linemen rides the lines—through forests and up mountains with flashlights if necessary—to locate the injury. In the Hendersonville case, an additional 1,500 customers would have lost power.

“With Smart Grid, you don’t have to worry,” says Huang, “because software and communication take over.”

But developing a Smart Grid system alone will not solve all the problems of the existing grid or eliminate the need for additional power lines to acquire electricity from renewable resources, Mohler says. “Ultimately, we need to do both.”