The pork production industry consolidates under China’s WH Group

BY DREE DEACON

When Chinese conglomerate WH Group bought Smithfield Foods in fall 2013, the purchase brought public attention to the growing demand for pork on a global scale.

The purchase also raised questions closer to the Smithfield, Va., home of the well-known pork company. Observers mulled the international ownership of a Southern-based foods company and the trickle-down effect on both contract and independent hog farmers, as well as on some of the environmental sustainability policies that Smithfield supports. In North Carolina, Smithfield is the primary player in the hog industry and operates the world’s largest pork processing plant.

Kathleen Kirkham, director of corporate communications at Smithfield Foods in Smithfield, Va., said the chief executive officer of WH Group, Wan Long, made several promises to Smithfield that certain practices, including strong efforts regarding sustainability, wouldn’t change as a result of the buyout.

“We believed him, but you’re also wondering, is this really true?” Kirkham said. At this point, the company has not seen any significant changes. “Our management teams are still in place, and all of our policies are still in place, so from a Smithfield standpoint, it’s sort of business as usual in the United States.”

As the demand for pork is seeing an international upsurge, led by China, the hog industry continues to consolidate, putting profits into fewer pockets. The environmental effects of hog production have occupied farmers, consumers and legislators during the last few decades, and now the decisions about how to deal with these effects are in the hands of fewer and larger corporations.

In light of consolidation across international markets and the emergence of expensive technology that can convert hog waste into renewable energy, the question becomes: Who will be responsible for bringing waste management technology innovations to the North Carolina hog industry, and when?

Moratorium prompts industry consolidation

In 1995, quite a few of the nation’s top hog producers operated in North Carolina, including Smithfield Foods, Murphy Family Farms, Carroll’s Foods, Prestage Farms and Continental Grain Company.

In 1997, the North Carolina Legislature issued a temporary moratorium that prevented building any new hog farms with 250 or more pigs or expanding existing large operations. In 1999 the N.C. Legislature revised the moratorium to prevent the building or expansion of hog farms that used the lagoon-and-spray method to dispose of hog waste. Ten years later, the Legislature made the moratorium permanent in Senate Bill 1465.

The moratorium intended to stop the damaging environmental effects of spraying hog waste as fertilizer on farmers’ fields in the wake of accelerating hog farm construction in the 1980s and early 1990s. Senate Bill 1465 outlined criteria by which new farms could be built and required the complete or at least substantial elimination of harmful discharges and emissions. To build or expand under the moratorium, growers need to install sustainability technology that meets specific environmental protection standards.

Studies have not yet found any such technology to be as cost-efficient as the lagoon-and-spray method. Alternative waste treatment options exist, some of which capture greenhouse gases to generate energy. Tom Butler, owner of Butler Farms and a contract grower for Prestage Farms, said sustainability initiatives on his farm cost more than $1 million. Most farmers find technologies like those Butler uses too expensive to install without outside financial support. The North Carolina Pork Council backs the lagoon-and-spray method as the most efficient way of disposing hog waste.

After the moratorium’s enactment, any corporate hog producer looking to expand found it much more economically sensible to buy existing hog farms to avoid the expense of innovative sustainability technology required by the moratorium’s regulations. For that reason, the moratorium sent the value of North Carolina hog farms soaring, Butler said.

Tom Butler has been raising hogs for Prestage Farms on his finishing farm in Harnett County since June of 1995. Photo by Kelly Creedon.

Now, WH Group might have plans to grow, even within the parameters of the moratorium.

As an observer of the hog industry, Mike Williams, director of the Animal and Poultry Waste Management Center at North Carolina State University, accepted an invitation from WH Group to visit and tour its facilities in China soon after the acquisition. There, he was asked to present his research on swine waste management, conducted by way of the Smithfield Agreement.

Williams said his visit and conversations with WH Group executives gave him “the clear impression that they would like to expand in North Carolina,…that they have an intent to grow. And they’re going to grow somewhere in the world.”

In addition, he noted, “My personal assessment is that their capacity to grow in China is limited for several reasons,” among them the dwindling amount of arable land in China, because of its rapid population growth.

Diminishing farmland might be a reason for WH Group to expand internationally, as it did with the Smithfield purchase. Expansion could also include buying additional foreign pork producers or expanding operations in North Carolina, other states or even other countries.

Keira Lombardo, WH Group’s vice president of investor relations and corporate communications in Hong Kong, said in an email that the company has nothing to announce at this time in regard to expansion.

While forecasts of the Chinese company’s expansion in the U.S. are unclear at this time, WH Group did make clear its intentions to ramp up exports from the U.S. to China, according to an April 2014 statement released in conjunction with a stock offering. WH Group’s Chinese hog production totaled 300,000 hogs in 2013. Smithfield’s U.S. hog production in 2013 topped out at 16.3 million, the release noted.

The release explained that WH Group “intend(s) to increase exports of U.S. chilled and frozen pork and by-products to China and other markets by leveraging our globally integrated platform and our competitive cost structure in the U.S.”

North Carolina already has a strong trade connection with China. North Carolina’s revenue from food products exported to China nearly doubled last year, from $132 million in 2012 to $251 million in 2013, according to the 2013 North Carolina Annual Trade Report conducted by the N.C. Department of Commerce.

Sustainability and the chance for growth

While WH Group officials aren’t saying anything specific about growth, others are speculating about how that could happen in North Carolina. Under the moratorium, a North Carolina expansion by WH Group would mean the company would have to ditch the lagoon-and-spray method of waste management and either integrate more expensive sustainability technology or find a way to make such technology more affordable for farmers.

“If they intend to grow in North Carolina with the current law, Senate Bill 1465, they have to incorporate technologies that would meet this criteria,” NCSU’s Williams said.

Alternative methods to the lagoon-and-spray approach include both on-farm and off-farm systems that separate liquid and solid waste and treat it, sometimes using the byproduct as fertilizer. Smithfield contributed $15 million to the testing process of these methods in a project known as the Smithfield Agreement, but no tested technology was found to come close to the economic feasibility of lagoons.

Kraig Westerbeek, vice president of environment and support operations at Murphy-Brown, a subsidiary of Smithfield, also visited WH Group’s Chinese farms after the acquisition. He said he got the impression that WH Group was looking toward additional waste treatment methods.

“It appeared to me that they encourage new technology that makes sense economically, which has always been our position,” Westerbeek said.

Each WH Group farm he visited in China had a biogas digester, which treats farm waste and produces biogas that can be used to generate renewable energy, Westerbeek said. “Any facility that I went to had a biogas digester on it, actually working,” he said. The U.S. had 157 digester projects, and only 24 were on swine farms, according to Environmental Protection Agency figures in 2010.

If expansion needs prompted WH Group to develop, use and maintain new technology at an affordable cost and implement that technology in the U.S., the company could build new hog farms in the state, the first since 1997. In that scenario, the value of existing hog farms that use the lagoon-and-spray method could drop. With the moratorium, hog farmers’ property is worth more because hog-producing companies that want to grow in North Carolina have had to buy or consolidate.

However, WH Group doesn’t have to expand in North Carolina. The company could also extend into other established agriculture areas that do not have a moratorium in place, like Iowa, the nation’s largest hog-producing state, or South America, said Kelly Zering, associate professor of agriculture and research economics at North Carolina State University.

Butler Farm manager Dave Hall prepares an empty barn for a new delivery of pigs. Photo by Caitlin Kleiboer

“Other U.S. states and other countries may provide a lower cost avenue for expansion,” Zering said. “The investment, tax base income, employment and trade will be created where the expansion occurs.”

So while Senate Bill 1465 was intended to give way to a more environmentally aware hog industry, it also created the possibility of cutting North Carolina out of trade opportunities and job creation, Zering said.

But Williams said that if WH Group does eventually expand its operations in North Carolina rather than elsewhere, that move would be far better for the environment on a global scale because expansion in North Carolina would not include waste pollution from lagoons. Now, though, there is no incentive, financial or otherwise, to invest the money it takes for the development of new technologies when the company could expand elsewhere cheaper, Williams said.

“It’s discouraging to me because, if our objective is to maintain animal production in this state, in this country, we really need to provide, in my view, incentives to get these technologies on the ground,” Williams said.

Without incentives, the polluting lagoon-and-spray method will spread to other areas of the world, Williams said.

In regard to whether the conglomerate will change any environmental aspects of Smithfield, like renewable energy initiatives or new waste management systems, Smithfield’s Kirkham reiterated that policies are still in place. “They’ve actually sort of left stuff alone,” she said. “In fact, the chairman (Wan Long), his message for us is ‘always continue to push further,’ so they want us to actually increase or sustainability program, not decrease it.”

Survival of the Fattest

BY BAILEY SEITTER

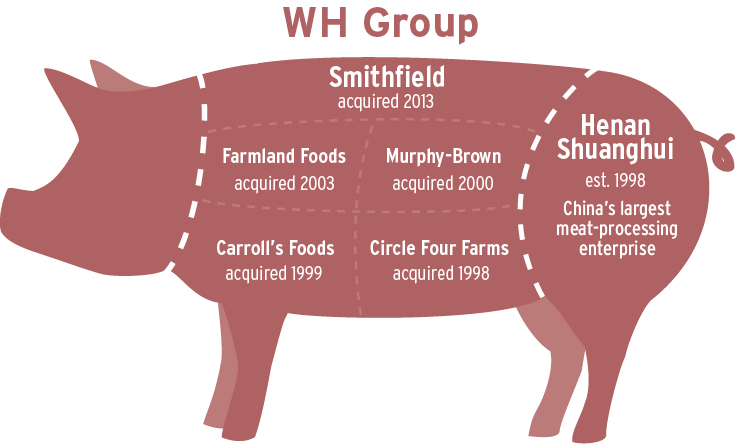

During the past 20 years, Smithfield Foods accumulated the nation’s top hog producers and processors. In 2013, Smithfield was purchased by Chinese conglomerate WH Group, majority owner of China’s largest meat-processing enterprise, Henan Shuanghui Investment and Development.

WH Group and Smithfield connect

When WH Group acquired Smithfield, it absorbed the largest pork producer in the United States. In North Carolina alone, Smithfield Foods saturates the pork production market, employing more than 10,000 people in the state. Prior to the acquisition, Smithfield had already done the work of consolidating and taking full advantage of the appreciation in hog farms’ worth as a result of the moratorium.

One year following the 1997 moratorium, Smithfield acquired Circle Four Farms, beginning a lengthy string of acquisitions by which Smithfield soaked up many of the largest pork producers and processors in the country.

In 1999, Smithfield bought Carroll’s Foods, the fourth-largest hog producer in the country at that time. A year later, Smithfield bought Murphy-Brown, formerly Murphy Farms, then the nation’s largest hog producer. In 2003, the company continued to swell, buying Farmland Foods, then the sixth-largest pork producer in the U.S.

Finally, in September 2013, the Chinese company WH Group swallowed Smithfield and all of its acquired subsidiaries and flexed its financial muscle.

WH Group, formerly Shuanghui International Holdings, acquired Smithfield Foods for $7.1 billion, or $4.7 billion without debt. Though incorporated in the Cayman Islands, WH Group is headquartered in Hong Kong and is the majority owner of China’s largest meat processing enterprise, Henan Shuanghui Investment and Development.

Since the acquisition, WH Group has retained most of Smithfield’s top executives, including chief executive officer Larry Pope and chief financial officer Robert Manly. Pope and Manly remain publicly adamant that the buyout will have only positive effects on Smithfield, asserting that almost nothing will change as a result of the sale to the Chinese company. Pope received $2.7 million in the form of a retention bonus and non-equity compensation from WH Group. Manly received $3.8 million as a retention.

Six months after WH Group assumed Smithfield’s $2.4 million in debt, the company filed an initial public offering in April 2014, looking to raise as much as $5.3 billion. The completion of the offering would have allowed WH Group to re-list Smithfield Foods in Hong Kong and sell shares publicly to help absorb the debt cost of the purchase.

WH Group’s Lombardo said the newly unified company was ready to go public.

“For many years prior to our merger with Smithfield, we established a sound cooperation and relationship between the two management teams. Through our active negotiations and exchange of views during the acquisition, we formulated a very mature plan for generating synergies. Therefore, we were ready to present ourselves as one company to potential investors,” Lombardo said.

Despite the company’s apparent willingness, the offer was later halved in price and then scrapped all together because of the company’s inability to raise enough capital from shareholder interest.

“In terms of plans for an IPO, the company has nothing to announce at this time,” Lombardo said. For now, the company remains privately held.

Prestage Farms workers load market-weight hogs for transport to the processing plant. Photo by Kelly Creedon

Operating outside a conglomerate

While some welcome WH Group, others have concerns. Steve Wing, associate professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, sees a dangerous trend in large-scale consolidation.

“The architecture of the system now puts the food supply in the hands of a small number of corporations,” Wing said, leaving the global food supply more susceptible to risks associated with extreme weather conditions, disease and contamination.

The reality of his statement is evident in the contagious and deadly PED hog virus, which has cut the number of commercially slaughtered hogs in North Carolina almost in half since last year, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics.

Consolidation under China could also threaten the market flexibility of the independent farmer in North Carolina, NCSU’s Zering said. Smithfield’s consolidation along the East Coast, prior to its acquisition by WH Group, presented challenges for independent growers in a more monopolized market.

Independent growers take on a greater financial risk in the absence of a guarantee that their hogs will be purchased for processing. Contract growers enter into contracts with integrators, like Prestage and Smithfield-owned Murphy-Brown, with the assurance that they will be paid for the hogs they raise, regardless of market conditions. However, if the market is favorable, independent growers can pocket a much larger cut of profit than can contract growers.

Independent farming is more popular in the Midwest U.S. than it is in North Carolina, largely because farmers in North Carolina have limited options in processing plants, said Summer Lanier, public relations director at Prestage Farms.

Lanier explained that processors require a minimum number of hogs in each load they buy. “Most people that would want to be independent would not meet that volume limit,” Lanier said.

James Lamb, a contract grower and environmental specialist at Prestage, said, “There might be a few small packing plants, but pretty much any large (pork) facility on the East Coast — Smithfield owns them all.”

Lamb, who grew up farming independent of an integrator, said he made the transition to contract farming because of the changing market.

“There used to be a couple of smaller slaughter facilities like in Spivey’s Corner, but over the years, they have vanished,” Lamb said. “So without a place to market your animals, it became a little challenging.”

Motivation to sign a contract with an integrator is largely financial.

“When I got out of college, it was very difficult,” Lamb said. “If I wanted to build a facility like I have now, it takes a huge amount of capital. When you’re 25 years old, it’s hard to stand in front of a bank and say you need a quarter of a million dollars.”

Competition for jobs in the consolidating hog industry can be intense on a national scale. The agriculture industry’s unemployment rate is consistently higher than the nonfarm unemployment rate, and it has been for more than 20 years.

However, the ideology behind independence can be equally motivating for a farmer.

Tom Butler, a contract farmer for Prestage in Harnett County, has never been an independent farmer, but he wishes he was.

“Independence is just the American way,” Butler said. “If I could be independent now, I would. But the way the model is made up, you can’t.”

“We’ve had several that have tried (independent farming), and they went bankrupt because it’s competition to the integrators,” Butler said.

Big profits keep flowing to the pork industry, but being a contract grower keeps him from seeing most of it, Butler said.

“There’s a lot of profit in pork,” Butler said. “And, of course, we’re not getting it.”

Butler Farms manager Dave Hall checks the feed bins for the operation’s 10 barns. Photo by Kelly Creedon

Additional stressors

Large-scale consolidation is not the only threat to independent farming.

Butler said the main difficulty in maintaining independence is the fluctuating price of hog feed, which makes up more than half the total cost of production.

For independent and contract farmers alike, maintaining any profitability with rising costs takes strategy and innovation. Federal regulations have indirect effects, and environmental regulations must be met.

For example in 2004, the Environmental Protection Agency enacted the Renewable Fuel Standard, which established regulations for blending gasoline with renewable fuels. Researchers deemed corn-based ethanol to be the safest and most economically viable alternative renewable fuel for blending with gasoline, which led to a booming ethanol industry and a high demand for corn. The consequences brought bad news to the hog industry, which relies on corn as the main ingredient in feed. The mandate put ethanol in direct competition with feed for corn harvests. The price of corn has doubled since 2004, according to a report by the University of Illinois.

While a potential step in the right direction environmentally, the mandate has economically hurt national hog production, Lanier said.

“It (ethanol) got over a quarter of the normal grain crop,” Lanier said.

The ethanol mandate put an economic strain on the industry, but large companies like Prestage and WH Group’s Smithfield-owned Murphy-Brown can absorb the risk and protect their contract growers from severe financial loss. Independent growers are not granted the same immunity from cost spikes in grain or any other aspect of production.

“For an integrator like us, that’s hard times, but we can weather the storm,” Lanier said. “For a small producer, that’s death.”

NCSU’s Zering said, “It’s in a farmer’s nature to be independent, but it takes a lot of resources these days.”

Smithfield routinely lobbies against the EPA’s ethanol mandate, according to lobbying disclosure forms filed with the N.C. Secretary of State’s Office.

Beyond just owning farms

When it bought Smithfield, WH Group also netted the company’s pork processing operations. In addition to growing most of the state’s hogs, Smithfield owns North Carolina’s two largest pork processing plants. The plant in Tar Heel, N.C., is the largest pork processing plant in the world. Smithfield’s contract growers rely on these plants, and so do contract growers for other integrators — or companies that employ hog farms — and independent farmers.

Prestage Farms, the nation’s largest family-owned pork producer, is one of few pork producers that maintained its ownership while Smithfield absorbed several of its competitors in the 1990s. Prestage is excited about the acquisition, said Prestage’s Lanier. The company relies on Smithfield’s processing plants, much like everyone in hog production in North Carolina.

“We are actually Smithfield Foods’ largest contract growers ourselves,” Lanier said. “This is not true of all of our divisions, but here in North Carolina, all of our pigs go to a Smithfield (processing) plant.”

Considering Smithfield’s trend of absorbing its contract-growing producers, it would seem that Prestage could be next on the list. But, Lanier said, Prestage isn’t interested.

“Prestage is committed to remaining a family-owned, family-operated business and has no interest in selling,” Lanier said. “We have weathered many times when others were selling out all around us, but we have remained.

“We are hoping that the Chinese acquisition will continue to open new doors for exports for our product because domestic demand is up, but it does not meet our current supply,” Lanier said.

United States pork consumption has remained relatively stagnant since 2010, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It does not match the current production of large companies like Smithfield, making it economically viable to seek more export opportunities. China consumes nearly half of the world’s pork, and Chinese pork consumption has increased 12 percent since 2010.

Processed hogs hang in the freezer at the Nahunta Pork Center in Pikesville, N.C. Photo by Kelly Creedon

WH Group also absorbed Smithfield’s agreement with the EPA that opened some farms to research. The EPA studies and mandates regulations pertaining directly to hog farms to reduce harmful effects from pollution, such as methane emanating from hog waste lagoons.

However, it is becoming increasingly challenging to gain access to corporate farms to carry out research that could give rise to new regulations, NCSU’s Williams said.

“It is absolutely critical to do some research and development on a commercial scale…and it is getting almost impossible to identify farms to do this work because producers don’t trust the government relative to the consequences,” Williams said.

Consequences of cooperation could take the form of new regulations or mandates, which are often costly. To alleviate this tension, the EPA reached out to Smithfield after the agency conducted a 2002 study that suffered from a general lack of data regarding commercial hog farms. The EPA offered Smithfield a consent agreement and order by which its participating hog farms’ owners and operators could agree to pay a penalty to the EPA, contribute to the cost of an air emissions monitoring study and make their farms available for observation, according to Smithfield Foods’ 2013 annual report.

In return, if air quality violations were found, participating farms would have immunity from federal civil enforcement actions, such as those under the federal Clean Air Act, according to the report.

Murphy-Brown’s Westerbeek said all Muphy-Brown company-owned farms, which are now WH Group-owned farms, have entered into this agreement with the EPA. WH Group’s Smithfield committed to pay the EPA $100,000, which covered the penalties for all of its company-owned farms in North Carolina and across the country, according to the report. The National Pork Board, of which Smithfield is a dues-paying member, covered the costs of this penalty on behalf of its participating hog producers, including Smithfield. The bill for all its member producers totaled $6 million.

The agreement brings the government and the corporatized hog industry into a close arrangement that some question, wondering if the government is truly aware of the livelihood of a farmer.

“The EPA people, they’re not really familiar with the day-to-day (farming) operations and shouldn’t be. That’s not what they do,” Butler said. “But they shouldn’t be making the rules either.”

Others think financially promoting this type of cooperation between the government and corporate hog producers, such as Smithfield and now WH Group, could facilitate more efficient research and, in turn, a better understanding of the effects of hog farming on the environment.

“I would like for the government to offer more of those types of guarantees,” Williams said in reference to Smithfield’s consent agreement with the EPA. “It would really help us to get some of the answers that we need.”

As the one-year anniversary of the purchase approaches, university researchers like Williams aren’t the only ones hoping for answers about how to protect the environment from waste pollution on hog farms. Some contract farmers who use renewable technologies are also hoping their efforts provide solutions to environmental problems.

“The integrators have the money, and we have the know-how and the ability to get it done,” Butler said about a creating a more sustainable agriculture industry.

“I’m sure you got up and put clothes on this morning and ate breakfast,” Lanier said. “All of that is because of a farmer. We all live in houses, we all put clothes on, we all eat. None of that happens without agriculture. It’s to all of our advantages — everybody’s. Whether you’re one of the 2 percent of Americans that are farmers or not, it’s to everybody’s advantage to make this work.”

© 2025 Powering a Nation

Theme by Anders Norén