Decades after the hog boom, one southeastern N.C. community wrestles with lasting transformations

TEXT BY JESS CLARK, VIDEO BY KELLY CREEDON

Duplin County has one of the highest concentrations of hogs in the United States — about 30 hogs for every person in the county. But Duplin wasn’t always so hog heavy. The rise of industrialized hog farming in the 1980s and ’90s inundated the county with pigs and their waste. This pork industry explosion fattened some pocketbooks, but it also drove a wedge through the community over odors, health and environmental effects. Now, decades later, residents’ class-action lawsuit against the world’s largest pork producer shows that, once pulled apart, it isn’t easy to put a community back together.

The lay of the land

In 1891 Elsie Herring’s grandfather, a freed slave, bought a tract of land from his former slave owner and aunt, a white woman he called Miss Emily. By 1897 he had bought about 70 acres in Duplin County — the same land that Herring’s mother would live on all 99 years of her life — the same land that Herring and her siblings would grow up on and that Herring would return to in 1993.

Now that land is the collateral damage of one of the most prosperous industries in Duplin County and southeastern North Carolina. While some see hog farming as the savior of the region’s economy after the collapse of the tobacco market, those facing the brunt of its health and environmental effects have a different take on the industry.

Like many farmers in southeastern North Carolina, Herring’s family grew tobacco — the region’s main cash crop. In 1950, at the height of tobacco’s reign, North Carolina produced 850 million pounds. But after the Surgeon General issued his first warning against the harmful effects of smoking, cigarette sales fell and continued to decline for the next four decades. In 2005, the federal government ended the price supports it had provided tobacco farmers since 1938. Between 1964 and 2012, the number of tobacco farmers in the state plummeted from more than 87,000 to just under 1,700. The decline of tobacco paved the way for the rise of what has become another controversial agricultural product.

Enter Wendell Murphy

In 1969 a successful Rose Hill hog farmer and feed producer named Wendell Murphy lost his entire herd when a cholera epidemic hit his farm. After the disease struck, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ordered all 3,000 of his hogs destroyed and quarantined the farm, forbidding the entry of any new pigs.

Unable to grow hogs on his own land, Murphy began looking for other options. He bought new pigs, wire and fence posts and paid his neighbors a dollar a pig to raise his hogs on their land. Contract hog farming was born in North Carolina.

By the 1990s, Murphy Farms had a waiting list of people eager to sign a hog-growing contract. Other companies like Prestage and Carroll Foods also adopted the contract model.

Most of today’s contract growers started out with land that had been in their families for generations — usually plots that were used to grow tobacco in the heyday of cigarette sales and were too small in the age of industrial agriculture to turn big profits by growing soybeans or corn. These small patches, however, proved perfect for concentrated hog farming. A farmer could put hundreds of pigs in one barn and build several barns on an old tobacco field. The farmer would dig lagoons near the barns to collect the waste and use the rest of the land as spray fields to dispose of waste when the lagoons filled up.

No such thing as a weekend

Mike Aldridge drives home from the Duplin County offices where he works as county manager. It’s finally evening, the phones were ringing all day, and he’s tired from multiple meetings. He parks next to his house while the sun is sitting low in the sky and goes inside. Through his back window he can see the hog houses at the back of his field: eight long barns, each filled with 720 pigs. Aldridge heads outside and makes his way towards the persistent “YING YING YING YING,” the mechanical sound of an empty feeder.

Like many contract hog farmers, Aldridge leads a sort of double life. He has an office job, what farmers call a “public job,” that provides a steady source of income and, most importantly, health insurance.

“It’s one of those necessities of life,” Aldridge said. “You’ve got to have insurance, and we don’t provide insurance on the farm.”

Aldridge said most hog farmers need a public job to make ends meet, or they have to diversify into other farming operations like corn, tobacco or cows.

But at the end of a long day at the office, the hogs still need to be cared for.

Pork reigns supreme

Advocates of the hog industry call it the economic backbone of rural counties in southeastern North Carolina. “Without the industry, Duplin wouldn’t even be on the map,” said Kennedy Thompson, chairman of the Duplin County Board of Commissioners. Thompson is a lawyer in Warsaw but at one time raised hogs as a contract grower for Carroll’s Foods, which has since been absorbed by Smithfield Foods.

Statistics show that as the population of hogs increased in North Carolina, gross income of hog farms increased from half a billion dollars in 1988 to more than $2.5 billion in 2012. Some estimate that as many as 46,000 jobs have been created directly and indirectly by the hog industry.

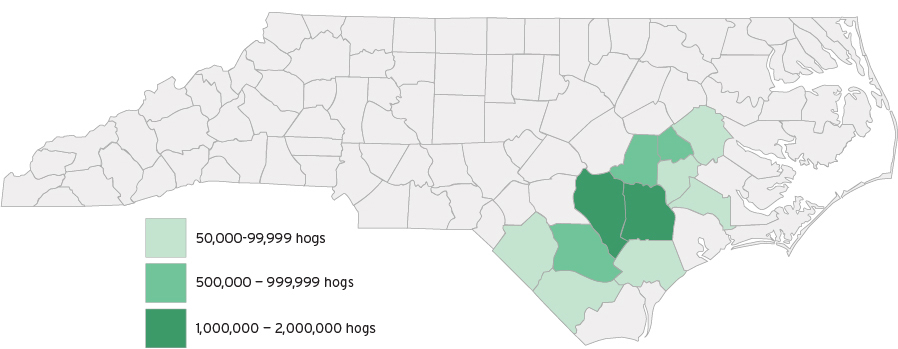

While not a huge employer by state figures, the pork industry directly employs more than 12,000 people in North Carolina, including workers on hog farms and in pork production jobs, such as those in meatpacking plants. Overall, that’s only 0.2 percent of North Carolina’s total employment. But 11,800 of those 12,000 employees work in an 11-county region in southern and eastern North Carolina. In those core 11 counties, one in 25 people works for the pork industry.

In the 11 counties highlighted, the vast majority of the state’s hog farming and processing activity takes place.

Source: “Identifying Opportunities and Impacts for New Uses of Hog Waste in Eastern North Carolina,” Economic Development Workshop, Department of City and Regional Planning, UNC-Chapel Hill.

In Duplin County the hog industry is a major employer — but it hasn’t exactly skyrocketed most county residents into a life of luxury. The average annual wages of a North Carolina hog farm worker are about $41,000. For those in pork production, average annual wages are just over $28,500. Duplin still remains among the poorest counties in North Carolina, with a 23.6 percent poverty rate.

Disparate outcomes for communities of color

While the pork industry has brought new wealth to some in southeastern North Carolina, African Americans have been overwhelmingly left out of the hog boom. Less than 2 percent of North Carolina hog farms are black-owned. Disparities in access to credit could be one reason there are so few black hog farmers in North Carolina. Contract farmers often take out hundreds of thousands of dollars in loans to build the hog houses, feeders and other infrastructure required. And historically across the U.S., some creditors have been cited for discriminating against people of color. For example, in 1999, the USDA agreed to pay out $1 billion to thousands of U.S. black farmers it had denied credit because of their race between 1981 and 1996.

But despite the low number of black hog farmers, some researchers say communities of color are disproportionately — and more highly — affected by the industry’s environmental impacts.

A 2000 study by researchers at East Carolina and Loyola universities found that controlling for other factors, swine operations were more likely to be located in low-income communities of color. In July 2013 more than 470 southeastern North Carolina residents filed complaints against Smithfield Foods and its subsidiary Murphy-Brown, accusing the companies of creating a nuisance, defined as “unreasonably interfering with their right to enjoy their personal property.” Nearly 90 percent of the plaintiffs are black.

A case decades in the making

Violet Branch awoke with a start between 2 and 3 in the morning in her house in Duplin County. No sound had awakened her, but the smell weighed heavy on her chest, as thick around her as the darkness inside her bedroom. She didn’t dare step outside for air — as bad as the stench was inside, she knew it would be worse outdoors. How the odor had crept in through her closed windows and doors from the nearby spray field, she didn’t know. She just knew she needed fresh air, but had no way to get it where she lived.

Branch called her son, and even though it was the middle of the night, he answered. He drove over and took his mother away from her house so that she could take a breath free of the smell of hog waste.

Branch is one of the plaintiffs in the nuisance lawsuit against Smithfield Foods and Murphy-Brown. The plaintiffs claim that the odors, gases, particulates, bacteria and other toxins emanating from nearby hog farms have made it impossible for them to enjoy their property as they had before the hog operations began. Branch has been living in her home since 1942. She said she believes the hog waste coming from the farm built nearby in the 1990s causes her breathing problems and high blood pressure. Her doctor told her that her lungs were scarred, and Branch said that sometimes the odor causes her to vomit as she walks to her mailbox.

Five miles away, Rene Miller said she can no longer hang her clothes out to dry on the line, cook outside, or even open her windows because of the stench of hog feces and the large black flies that she said have swarmed in her yard only after the neighboring hog operation cropped up.

Miller, also a plaintiff, said in her affidavit that she suffers from asthma, sinus problems and sarcoidosis, a potentially fatal inflammatory lung condition. None plagued her before the hog farms were built.

Hog country residents like Branch, Miller and Elsie Herring have been dealing with the stench and its effects for decades now. Many say they were not able to initiate legal action sooner because area lawyers were not willing to take on the industry.

“The majority of people (in Duplin) got work with the hog farms. A Duplin county lawyer is not going to help us,” Miller said. “You could have had all the money you want to.”

Smithfield said in its 2013 annual report that it considers the plaintiffs’ claims “unfounded” and has plans to defend the suit “vigorously.”

Hog waste and human health

UNC School of Public Health researcher Steve Wing said there was initial reluctance on the part of the industry to admit the possibility that putting fecal matter into the air could have a negative impact on public health.

“In the ‘90s, people were saying, ‘This stuff is making me sick; it’s making my kid sick.’ And they were being told, ‘It’s just a little odor, it doesn’t have any health impacts,’” Wing said.

Now dozens of studies make the connection between hog waste and respiratory symptoms hard to deny. Among them, a 2000 National Institutes of Health-funded study by North Carolina researchers, including Wing, used a statewide survey of North Carolina students to determine that adolescents who could smell livestock odor inside their school buildings also reported 24 percent higher rates of asthma and wheezing. The researchers also found a 5 percent increase in asthma rates among adolescents who attended school within three miles of a hog operation.

Scientists in the country’s No. 1 hog-producing state have similar findings: A 2013 University of Iowa study showed that children in a rural county who lived or went to school within two miles of a pig farm with more than 500 animals and that used pits to dispose of manure were significantly more likely to be prescribed asthma or wheezing medication by their doctors.

The National Pork Board has responded to studies in the past that showed a correlation between asthma and proximity to hog operations. The board’s response to an earlier 2005 University of Iowa study that showed increased asthma among children living near swine operations notes that “as recognized by the authors, asthma risk is conveyed by a complex interaction of genetic and environmental determinants.” The study’s author, James A. Merchant, acknowledged the complexity of factors involved in asthma but maintained his belief that “some of the increase in asthma risk is related to occupational and bystander exposures in animal feeding operations.”

Wing’s own research found a correlation between increased systolic blood pressure and higher measures of hydrogen sulfide, a noxious gas produced by the decomposition of organic material in hog waste. His research also shows that higher levels of airborne hog waste toxins are positively correlated with heightened stress, anxiety and depression.

Researchers have documented other symptoms connected to living near hog operations, many of them gastrointestinal. In 2014, researchers at UNC-Chapel Hill stumbled across an unusual concentration of eosinophilic esophagitis in high hog-producing counties in North Carolina. This immune or allergic condition causes swelling of the esophagus, choking and difficulty in swallowing. Researchers were continuing to analyze and quantify the correlation as of May 2014.

The workers on hog operations face additional health risks. In 2011 Johns Hopkins University and UNC-Chapel Hill researchers found higher levels of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the nostrils of industrial hog farm workers than in the nostrils of workers who raise hogs outdoors, in pasture and without administering antibiotics.

While research can identify correlations between hog waste and health effects, what attracts less attention is the impact on the overall quality of life within communities near the farm operations, which, Wing says, is equally important.

“Their daily routines — especially rural people who have more expectations of spending time outside — those activities are disrupted on a daily basis.”

The community reacts

Area residents like Herring have been organizing for decades against the hog industry’s waste management practices. In 2002 Duplin County resident Devon Hall founded the Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help (REACH). The REACH office is in a double-wide trailer in Warsaw, N.C., in the heart of hog country. The members hold community meetings one evening a month there, led by Hall, a thin, energetic African American man, never seen without a ball cap over his white hair and his Bluetooth fixed to his right ear.

When Hall started REACH, community members didn’t think they could do anything about the odorous hog operations cropping up around their homes. But REACH began coordinating with other activists to spread information and create safe spaces for community members to share their concerns and connect with researchers.

In 2007 REACH helped organized a protest at the Legislative Building in Raleigh. Along a path legislators usually took between buildings, they built a replica of an industrial hog operation, complete with two kiddie pools they filled with 40 gallons of hog waste, meant to represent the lagoons. Naeema Muhammad, a long-time activist who helped organize the protest, said a maintenance worker threatened to call security on them.

“He said, ‘If you get one drop of that toxic waste on my lawn, I’m going to call security,’” Muhammad laughed. “They tell us it’s ‘organic fertilizer’ in Duplin. But once we got to Raleigh it was ‘toxic waste.’”

The protesters set up a sprinkler to spray the waste across the lawn, much like it is sprayed across fields near their homes. Muhammad said the legislators took a different path to avoid the smell.

Hall said the political and economic weight the pork industry has in the region can make it difficult to organize against its practices. Local politicians and business leaders often have connections to hog farming, so it can be intimidating for community members to criticize the industry. Hall noted a time when even a worker at the Division of Water Quality (now Division of Water Resources) in Wilmington didn’t follow protocol for protecting anonymous reporting of waste management violations.

Hall said a couple years ago, he called in an anonymous report about a hog farmer’s clean water violation, only to receive a call from the same farmer later that evening.

“When I said, ‘Hello?’ he said, ‘Who is this?’ And I’m saying, ‘Uh, who are you? You called me!’” Hall said.

Hall suspected that someone at the division offices had given the contract grower his telephone number.

He immediately called the office. “They dropped the ball,” he said he told the office staff. “They were not supposed to give out my number.”

Hall said the division sent him a letter of apology, which he still has tacked to the wall inside the REACH trailer.

Land of Lagoons

GRAPHIC BY BAILEY SEITTER

Lagoons are a controversial way to manage hog waste, so why do farmers use them? And what does North Carolina’s preference for lagoons mean for the hog industry’s carbon impact?

Sources: USDA Census of Agriculture, University of Arkansas’ “National Life Cycle Carbon Footprint for Production of U.S. Swine”, AccessScience, National Geographic

Water woes

While some activists have been more visible and vocal, others make their points about the impact of hog farms on communities and the environment in different ways. Larry Baldwin is covered in sweat. A big guy — 6-foot-5, 270 pounds — Baldwin has somehow managed to fold all his limbs into the backseat of a four-seater Piper Turbo Arrow, the cabin of which is no bigger than the inside of a pickup truck. It’s 10 a.m. and already 90 degrees on the tarmac, the temperature baking the inside of the plane as the pilot Dennis Howard prepares for takeoff.

“CLEAR PROP!” Howard yells. The plane begins to roll faster and faster along the runway. Baldwin still has one long leg out the open door to get some airflow, and he slams it shut just before the plane lifts into the hot air and heads due west from New Bern towards Duplin County.

Baldwin and Howard make this trip several times a month. Baldwin is the former Riverkeeper for the Lower Neuse, nicknamed the “Neuse Juice” because of the nasty concoction of runoff it gets from farms and industry. Now his job is to keep an eye on confined animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, to make sure they comply with federal Clean Water Act regulations.

Howard volunteers his plane so that Baldwin, as CAFO coordinator for the Waterkeeper Alliance, can get a view from the sky of the thousands of barns, lagoons and spray fields in Duplin, Sampson and other high hog and poultry producing counties in southeastern North Carolina. He and Howard are looking for evidence of lagoon overflow, eroded spray fields, improper burial of dead livestock, or improper spraying of waste, such as onto roads or into streams. For each infraction they spot, they file a complaint with the N.C. Division of Water Resources regional office in Wilmington.

On the ground, driving through Duplin County, it’s apparent that you are in hog country. Highway 24 from Warsaw to Kenansville is lined with fields, long metal barns clustered together at the back. At times the scent of something sulphurous, pungent and vaguely corny — the smell of hog waste — assaults the nose.

But from the air, the concentration of industrial agriculture becomes a thousand times clearer.

From 16,000 feet up, Duplin County looks like a patchwork of green and brown fields studded with clusters of long, rectangular barns and gleaming hog-waste lagoons.

“Sometimes when the sun is out, you can see them (lagoons) all lit up and shimmering,” Howard says into his headset.

Today is one of those days. The sun glints off the dozens of hog lagoons seen from the plane at any given time. When the angle of the sun changes, the lagoons aren’t blue, green, or even brown — they’re pink, Pepto-bismol pink.

“Look there!” Baldwin shouts. “He’s spraying right onto the road!”

Howard gives the plane a nudge and sends it into a sickening and exhilarating turn, circling lower so that Baldwin can get a better look. Indeed the mist from a sprayer has made a shadowy arc onto the roadway.

Baldwin pulls out a notebook and scribbles the details of the location and the infraction. In this case, by the time Division of Water Resources officials checked out the scene on the ground, no clear evidence of the violation remained, but they warned the farmer to make sure the sprayer wasn’t too close to the road. Baldwin said this outcome was typical: A DWR investigator couldn’t get to the scene while a sprayer was still on or the road was still wet. As a result, Baldwin estimates that only about 30 percent of the violations they report result in enforcement.

Overall, the hog industry in North Carolina is largely compliant with water regulations. Out of the state’s 2,217 hog farms, only two were penalized by the Division of Water Resources with fines in 2013. The DWR fined four North Carolina hog farms in 2012. According to Smithfield’s web site, none of Murphy-Brown’s company-owned farms received notices of violation of environmental standards in 2012 or 2013.

But even abiding by state and federal environmental regulations might not be enough to protect the area’s waterways from significant damage from run off, said Hans Paerl, a UNC-Chapel Hill marine biologist who studies the effect of agricultural run off into estuaries such as the Neuse River.

Hog waste contains high levels of nitrogen, said Paerl. That nitrogen makes its way into waterways either as runoff from spray fields or as ammonia gas that rises off lagoons in evaporation and comes back down to the Earth with rain, snow or ice. Lagoons themselves have been shown to leak nitrogen and other contaminants into the soil.

When that nitrogen reaches waterways, it feeds an overgrowth of algae called an “algae bloom.” Paerl said these blooms suck up the oxygen that fish and other creatures need to survive, throwing the whole water ecosystem out of whack.

Paerl said that limits from the state Department of Natural Resources on the amount of nitrogen released into the Neuse have significantly decreased the amount of pollution from human and industrial waste. But he has not seen a significant reduction in pollution from agricultural waste.

Feeling the tension

Activists who continue to lobby for changes through speech, protest, aerial monitoring and lawsuits say their fight isn’t against the hog farmers themselves. Farmers are “between a rock and a hard place,” said REACH’s Hall. The community isn’t upset because farmers aren’t following environmental regulations. The overwhelming majority of farmers do abide by the standards that are in place.

And county manager and hog farmer Mike Aldridge said breaking environmental regulations is a risk contract farmers can’t afford to take:

“Nobody’s telling their neighbor, ‘Oh what a great job they’re doing, they don’t spray when I’m having a family picnic, or they’re trying to do things appropriately for the crop, for the time of the year, I don’t see water ponding at the end of the road.’ They ain’t gonna tell the good things that you do, but you do something wrong one time, and they’ll tell everybody they know. So the industry and the farmer can’t risk it, there’s too much at stake. Because where would I go to get another contract? There’s one game in town and that’s Smithfield Foods. And if you screw that up, you’re out.”

Hall said he believes that contract growers like Aldridge are trying to provide for their families, but to do so within the system, they have to adopt waste management practices that, while legal, still have negative impacts on the surrounding community. The problem, as Hall, Muhammad and others see it, is that the regulations do not protect the community.

One reason, Hall noted, is that the industry’s strong lobby at the state and federal levels has kept “these laws so relaxed.”

In spite of tensions, community members on both sides of the issue share a heritage that revolves around pork as a central element of sustenance and family life.

“I love pork, I grew up eating pork,” Herring said. “My dad prepared to make sure that we always had plenty to eat. And we would kill hogs, and we’d have a smokehouse full of pork.”

When Herring was growing up, her parents kept hogs in a pen by her sister’s house and fed them on table scraps, corn and soybeans. When the weather turned cold, Herring’s father and uncle slaughtered the hogs and hung them to drain from a pole in the yard. Then the family would clean the hogs together. Herring remembered reaching into the hog’s split carcass to remove the liver for pudding and the intestines for chitlins. The meat they cleaned and prepared during the hog killing days kept Herring’s family fed throughout the year.

“There were so many of us,” Herring said. “We knew this was how we were going to live — because after awhile you do this so many times, year in and year out, you know what to expect.”