What happens when a river stops before the ocean?

By NATALIE TAYLOR

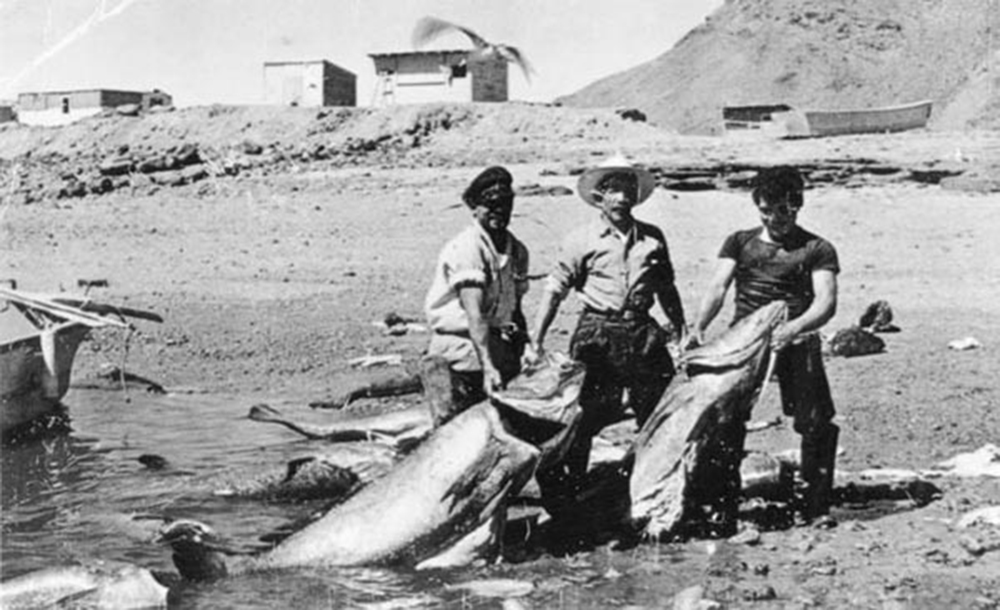

Tucked away in scrapbooks in northern Mexico, photographs from the 1930s show astonished men hugging fish as big as themselves. The fish, which can weigh more than 300 pounds, are called totoaba. They live exclusively in a 300-mile wide zone in the upper Gulf of California, in waters between the Baja Peninsula and mainland Mexico.

Left to right, Tony Reyes, Gorgonio Fernandez, and his son, Chi Chi Fernandez, with a totoaba catch, Baja California, Mexico, c. 1954.

Photo courtesy of The Unforgettable Sea of Cortez by Gene Kira.

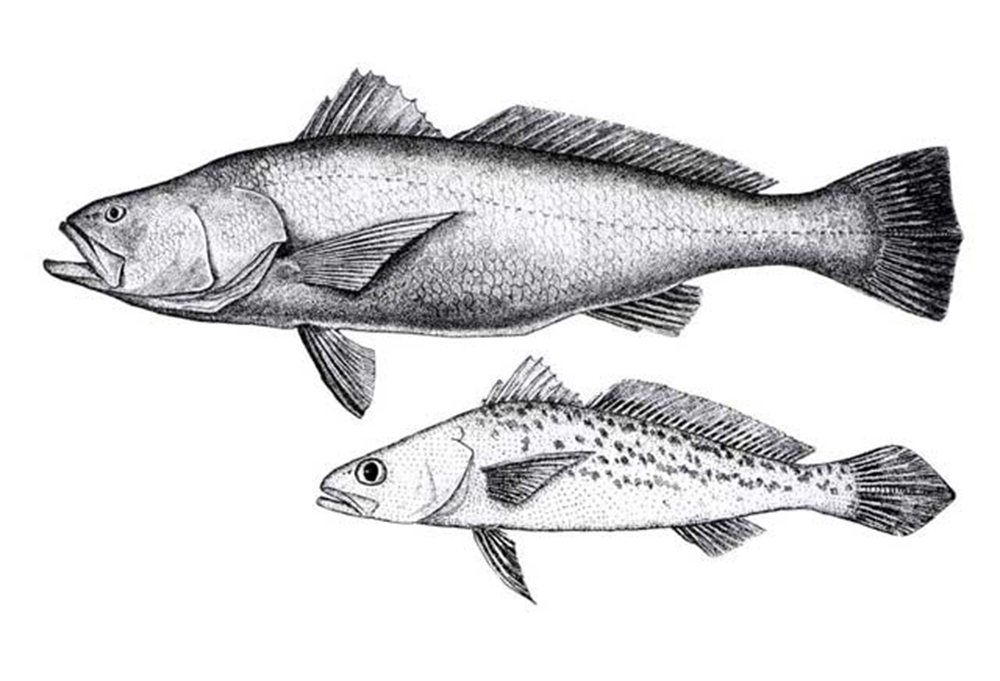

The totoaba is an unusual fish. Its mouth is on the underside of its head, and its disproportionately small eyes give the fish the appearance of permanent dismay, as though you have just taken its glasses. A member of the drum family, it uses special muscles to strike an organ called a swim bladder, making a drumming sound. Most fish use swim bladders for buoyancy; this species of drum uses them as an instrument.

Every spring for millions of years, the totoaba converged on the Colorado River delta. At that time of year, the river was laden with the minerals, silt and nutrients that ran off the watershed, an area about the size of France. By the time the river passed the delta to reach the Gulf of California, it had become a soup, its contents a critical part of countless food chains. There, the organic matter from the river nourished the young totoaba. The plume of sediment from the river protected them from predators that were not adapted for such darkness.

“Fishermen fed their families on the money from the dried bladders rather than the meat of the giant fish itself.”

Throughout the 20th century, as U.S. politicians negotiated and signed agreements and laborers banked and diverted water upstream, the totoaba headed toward extinction. They continued to spawn in the delta, where fishermen easily hauled them in flagrante into their boats. Their swim bladders were (and still are) an ingredient in a Chinese soup called Seen Kow, considered a delicacy. Fishermen fed their families on the money from the dried bladders rather than the meat of the giant fish itself.

A market for the meat developed in the U.S., and sport fishermen started vacationing at the Gulf of California. In 1942, fishermen caught 2,000 metric tons of totoaba, in 1958, only 300 and by 1975, only 58 tons. After that, the Mexican government completely banned totoaba fishing.

Feeding the U.S. market for fish and the Chinese market for delicacies helped decimate the population. The totoaba was caught in the crosshairs of overfishing and habitat destruction. Upstream diversions such as the Hoover Dam had disrupted the river’s pulse since the 1930s, and water consumption had kept the Colorado River from regularly reaching the sea since the 1960s, cutting off the ingredients so essential to the fish’s reproduction and growth.

Totoaba macdonaldi. Image by Alex Kerstitch.

Copyright Shorefishes of the tropical eastern Pacific online information system, used with permission.

Today, totoaba are critically endangered. Their plight represents the far-reaching impact dams and other water diversions along the Colorado River have had on wildlife. For the totoaba, the obvious villains are poachers who ignore the totoaba’s endangered status and smuggle them into the U.S. where each bladder sells for hundreds of dollars. The less obvious culprit is the lack of freshwater. But hope for the delta flickers in a recent agreement between the U.S. and Mexico to release more water downstream. To begin to understand why the Colorado no longer reaches the ocean requires a look upstream to Lake Mead, which as of this writing holds only half its capacity.

Ordering Water

“I feel like Superman.”

Bruce Williams thinks of the reservoir he manages as half-full. He is an optimist in the face of projected differences between the river’s supply and human water demands. As the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Manager of the River Operations Group at Hoover Dam, which retains the water of Lake Mead, he controls the water flow out of Hoover Dam to the Lower Basin states. Williams acknowledges that in some respects, he has the economy of the Southwest at his fingertips. “I feel like Superman,” he says of his position.

View of Black Canyon, Colorado River, Hoover Dam and Lake Mead.

Photo by Doc Searls, 2012.

Each year, the seven states of the Colorado River basin, as well as Native American nations and Mexico, are allocated a certain amount of water under the Law of the River, a bundle of laws, contracts, compacts and amendments that long ago estimated how much water ran through the river and now dictates how much of that water states can take.

Laws have been structured over the years so that certain users, such as the Imperial Valley in California, have rights to the water ahead of other users. Called “prior appropriation rights,” states upstream in the so-called Upper Basin can take their allotment but are beholden by the Law of the River to deliver the amount of water that downstream users have negotiated for themselves.

Williams and his colleagues who release the water think of themselves as water wholesalers; others call them water accountants. Either way, water is treated as a commodity, directed downstream from its reserves in Lake Mead. Williams notes that the Upper Basin has never failed to send water to the Lower Basin, despite a 14-year drought.

When a user that has a contract, such as a city, places a water order, Williams documents the water’s release and subtracts that amount from that user’s allotment. That means double and triple checking a daily water log along with other tasks such as maintaining water gauges along the river. Williams also communicates with operators at a cascade of dams and diversions that stand in the way of that water order getting from Lake Mead to a sprinkler head above a field of carrots in the Imperial Valley, California.

Williams, who has spent 30 years with the USBR, says he feels like the river’s caretaker. He answers to the Secretary of the Interior following orders to make sure the Law of the River is obeyed and releases water to downstream users. But no one orders water so that the Colorado River can reach the sea.

Life of the Delta

“Everybody has a water right but the Colorado River itself.”

“Everybody has a water right but the Colorado River itself, and that’s ethically and fundamentally wrong,” says John Weisheit, passionate advocate and director for the non-profit Living Rivers.

Other prominent voices in support of the river blame an accident of geography—the fact that the Colorado crosses into Mexico before hitting the Gulf of California—for the failure of the river to join its delta completely.

“Depletions have perhaps even more serious impacts on the river and its associated ecosystems as it travels its last few miles in Mexico,” writes Robert Adler in his book Restoring Colorado River Ecosystem.

“If the Colorado River delta were completely within the boundaries of the U.S., we would consider it a disgrace that the river didn’t reach the sea.”

“If the Colorado River delta were completely within the boundaries of the U.S., we would consider it a disgrace that the river didn’t reach the sea,” says Karl Flessa, director of the School of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Arizona. Because the Colorado ends outside U.S. borders, “it almost doesn’t feel like one of their responsibilities.”

No ecological surveys were conducted of the river before the dams began going up in the early to mid-1900s, and Flessa jokes that with his research, he is trying to reconstruct how the Colorado looked in the pre-DAMbrian era. If the river were flowing normally, the delta beaches would be constantly remade – eroded by the sea and renewed by the sediment washed down from the upstream canyons. This same sediment would nourish species like the totoaba, and many others.

“When a troop of egrets settled on a far green willow, they look like a premature snowstorm.”

Through the voice of Aldo Leopold in The Green Lagoons, author Adler depicts how Leopold described a “verdant wall of mesquite and willow [that] separated the channel from the thorny desert beyond,” saying “when a troop of egrets settled on a far green willow, they look like a premature snowstorm.”

At 2 million acres, the once-immense delta was a wetland habitat the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined, a crucial home for countless species of birds and other wildlife. The delta is now about 150,000 acres, 7.5 percent of what it used to be.

Flessa describes the section of delta that still exist as a “green oasis of willow and cottonwoods,” home to thousands of bird species. No longer bordered by the desert, the oasis is instead surrounded by its agricultural successors: fields of alfalfa, wheat or onion—economic endeavors irrigated 100 percent by river water.

Today, the delta beaches are almost exclusively made of masses of clam shells that attest to the fertility of the delta when the Colorado reached the gulf. Now that the sediment is trapped behind the dams, the tides have washed the clams out of the sediment and accumulated them on the beach. “They crunch when you walk on them,” Flessa says.

The decline of the totoaba is less visible. Ecologist Kirsten Rowell has other means of determining the extent of the damage to the fish since the nutrient-rich river silt has been blocked from the delta. She uses otoliths, the ear bones of fish, to quantify what the Colorado River meant for the totoaba. A fish’s otolith looks like an iridescent, ridged contact lens. Concentric rings, like tree rings, reveal a fish’s age and hint about elements of its life. Comparing the otoliths she found in Native American middens (trash piles) from 5,000 years ago, Rowell has shown that the ancient totoaba grew twice as fast and matured two times earlier in the estuary of the Colorado River when it reached the ocean.

“Because the river terminates in a foreign country…it is suffering a slow death.”

“If the final reaches of this 6-million-year-old delta were in the United States, they would have been declared a national park, with a protected free-flowing river,” wrote Jon Waterman in an op-ed in The New York Times in 2012. “But because the river terminates in a foreign country, beyond the reach of the Endangered Species Act and most tourists’ cameras, it is suffering a slow death.”

Minute 319

While many have written about the dire situation in the delta, hope in forestalling its death lies in recent negotiations between the U.S. and Mexico on the Law of the River.

In December 2012, representatives from the U.S. and Mexico met in a hotel ballroom in San Diego to discuss and sign the most far-sighted amendments to the Law of the River seen yet. It had taken years to get there.

Amendments to the Law of the River are called Minutes. Minute 319 is an agreement between Mexico and the U.S. over water that ignores their borders and contains several revolutionary points. First, owing to an earthquake that destroyed much of its infrastructure in 2010, Mexico will now store its 1.5 million acre-feet allocation in Lake Mead. Storing the water can help offset a water shortage declaration. As of this writing, the current lake level in Lake Mead was 47 percent of capacity and 31 feet away from a shortage being declared. Storing Mexico’s water allotment will raise the water level by 15 feet.

Second, Mexico and the U.S. have agreed to share in any future water shortages. This decision is significant; in the event of water scarcity, the U.S. would give up some of its water to provide sufficient water for Mexico. In return, Mexico would be willing to accept less water than promised. The agreement is groundbreaking because as opposed to the squabbling that characterized previous negotiations, Minute 319 emphasizes a sense of community around a single watershed.

“This negotiated solution takes steps toward working that out with an incredible shift towards flexibility around that border. It is really ground breaking in that sense,” says Jennifer Pitt, who took part in the discussions on behalf of the Environmental Defense Fund, a large non-profit concerned with the delta.

“Perhaps the most revolutionary provision within Minute 319 sets aside 105,392 acre-feet of water solely for the environment.”

Perhaps the most revolutionary provision within Minute 319 sets aside 105,392 acre-feet of water solely for the environment, the first time an international treaty has set aside water for such benefit.

In a one-time event, managers will release water to the river in 2014 to mimic a spring flood event. The release is expected to provide enough water for the Colorado River to flow over the delta, and for the first time in 15 years, water from the Colorado River will reach the Gulf of California. Observers believe the release will benefit many species in unpredictable ways, and others hope that the local, Mexican economy will also flourish. Small businesses already established along the upper Gulf, fish camps and bird-watching tours are waiting.

Minute 319 is set to expire in five years, but it is a tentative step towards recognizing the value of a river reaching the ocean. It represents the power of negotiation and trust, observers say. After water managers at Lake Mead fill the order for the pulse flow to create the spring flood, scientists will closely study the pulse’s effect on the species that inhabit stretches of the river and upper delta. While they will not focus on the oceanic species, what they learn above the delta is intrinsically linked to the ocean-going species, including the totoaba, in the Gulf of California.

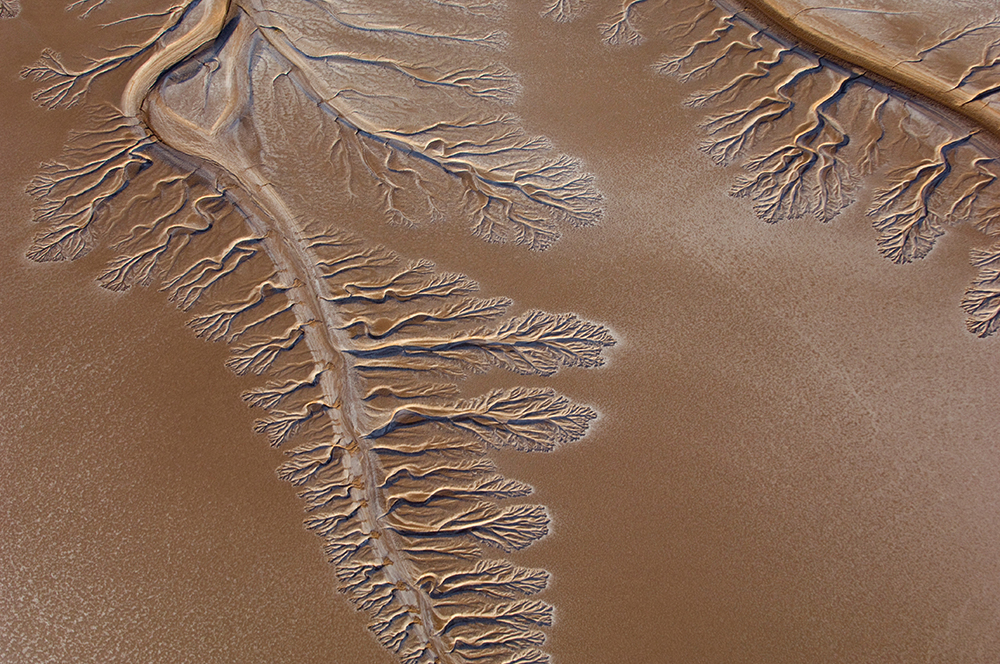

The now-dry Colorado River delta branches into the Baja/Sonoran Desert five miles north of the Gulf of California, Mexico.

Photo by Pete McBride, U.S. Geological Survey, 2009.

Like water manager Bruce Williams, paleoecologist Karl Flessa is also an optimist. He estimates that with consistent freshwater from the Colorado flowing into the sea, in a couple of years the shrimp population could increase, and in five years, the numbers of catchable fish.

Flessa expresses hope that populations of endangered species like the totoaba would bounce back. “I think there’s potential for that,” he says. “A little bit of water can have an enormous environmental benefit, and that environmental benefit can get translated into economic opportunities for people. We can’t quite turn the clock back, but the system as a whole is remarkably resilient.”

Sources:

2013 America’s Most Endangered Rivers. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.americanrivers.org/assets/pdfs/mer-2013/2013-report.pdf

Adler, R. (2007). Restoring Colorado River Ecosystems: A Troubled Sense of Immensity. Washington, D.C.:Island Press.

Alles, D. (2012). The Delta of the Colorado River. Retrieved from http://www.biol.wwu.edu/trent/alles/TheDelta.pdf

Blue Legacy. (2012). Historic agreement creates momentum for the restoration of the colorado river delta. Retrieved July 02, 2013, from http://www.alexandracousteau.org/blog/momentum-in-restoration-of-colorado-river-delta

Dwyer, C. (2012, December). Colorado River Basin Water Supply & Demand Study: Final Study Reports. Retrieved July 2, 2012, from United States Bureau of Reclamation’s website: http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/programs/crbstudy/finalreport/

Earstones tell fishes’ tale in colorado river estuary. (2004, June 15). Retrieved from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2004/06/040614081436.htm

Erisman, B., Aburto-Oropeza, O., Gonzalez-Abraham, C., Mascarenas-Osorio, I., Moreno-Baez, M., & Hastings, P. (2012). Spatio-temporal dynamics of a fish spawning aggregation and its fishery in the gulf of california. Scientific Reports, Retrieved from http://www.readcube.com/articles/10.1038/srep00284

Fountain, H. (2013, April 15). Relief for a Parched Delta. The New York Times, pp. D1.

Kira, G. (1999). The Unforgettable Sea of Cortez: Baja California’s Golden Age, 1947-1977: The Life and Writings of Ray Cannon. Torrace, CA: Cortez Publications.

Leopold, A. (1966). A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press, Inc.

NOAA Fisheries. (2012, December 5). Totoaba. Retrieved July 2, 2012, from NOAA Fisheries’ website: http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/fish/totoaba.htm

Rowell, K., & Dettman, D. (2008, November). Coming together: coordination of science and restoration activities for the colorado river ecosystem. , Scottsdale, Arizona.

Secretary slazar releases colorado river basin study projecting major imbalances in water supply and demand. (2012, December 12). Retrieved from http://www.doi.gov/news/pressreleases/secretary-salazar-releases-colorado-river-basin-study-projecting-major-imbalances-in-water-supply-and-demand.cfm

The colorado river’s last great desert wetland. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.edf.org/ecosystems/colorado-river’s-last-great-desert-wetland

Water Education Foundation: River Report: Minute 319: Building on the Past to Provide for the Future. (2013) Retrieved from https://www.watereducation.org/userfiles/RiverReport_Winter13_web.pdf

Water Operations Control Center. (2013, June 28). Lower Colorado River Operations Schedule. Retrieved July 2, 2012, from United States Bureau of Reclamation’s website: http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/hourly/rivops.html

Waterman J. (2012, February 14). Where the Colorado Runs Dry. The New York Times. pp. A25.

Kerstitch, A. (Artist). Totoaba macdonaldi [Web Drawing]. Retrieved from http://biogeodb.stri.si.edu/sftep/taxon_mod_largepic.php?id=2386

McBride, P. (Photographer). (2009, January 12). Colorado River Dry Delta [Print

Photo]. Retrieved from http://gallery.usgs.gov/photos/10_15_2010_rvm8Pdc55J_10_15_2010_0

Searls, D. (Photographer). (2012, October 18). Black Canyon, Colorado River, Hoover Dam & Lake Mead AZ/NV [Web Photo]. Retrieved from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Black_Canyon,_Hoover_Dam_&_Lake_Mead_AZNV.jpg