How the West’s Water was Won

By NATALIE TAYLOR

John Wesley Powell was stuck. The man who would one day be hailed as a legendary explorer, geologist, ethnographer and visionary found himself braced halfway up cliff, in a crevice thousands of feet above the Colorado River, looking for a way higher.

The nine men waiting below were the remnants of Powell’s Colorado River Exploring Expedition of 1869. Powell had started climbing the cliffs in search of sap from the pine trees lining the top of the canyon in order to caulk the boats battered by the rapids of Cataract Canyon. Many in the group, including Powell, were veterans of the Civil War. Having withstood the agonies of battle, they were again fighting daily hardships—near-drownings, crushed boats and dwindling, mealy rations—to fill in the last remaining blank spot on maps of North America.

Major Powell Descends the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, 1869.

Painting by Henry C Pitz, 1935-1939. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Unable to go up or down, Powell went sideways, further into the crevice in which he was wedged. There he rested, then climbed, emerging to a sky free from the confining canyon walls. The river, thousands of feet below, had over millions of years carved the canyons that unfolded before him to the horizon, foretelling the journey Powell and his men had compelled themselves to complete.

This expedition, and later Western forays, would lead to Powell’s understanding that water would be the limiting factor in developing the West, and to his questions about who should determine how the precious water would be used. His observations of the river’s capacities would foreshadow the misuse and diversion that would occur within decades and fundamentally change the river’s course through its canyons.

The Coming Storm

As Powell stood on the brink of the cliff in July of 1869, he saw a storm coming from the south.

I seek shelter in the rocks; but when the storm bursts, it comes down as a flood from the heavens,— not with gentle drops at first, slowly increasing in quantity, but as if suddenly poured out. I am thoroughly drenched and almost washed away.

Powell’s words, written years later, are a vivid account of nature’s violence. Though a small incident in the life of a canyon, such a deluge could be life-threatening for Powell and his men. Recognizing the storm’s force, Powell descended the cliffs.

Traveling as fast as I can run … the water is running down a dry bed of sand … I hasten to camp and tell the men there is a river coming down the canyon … We carry our camp equipage hastily from the bank … then stand back and see the river roll on to join the Colorado.

Desert storms, like the one Powell encountered, are quick and destructive. Arid desert soils do not absorb rains, and when amassed rainwater encounters a canyon, its velocity and power can bring down the upper walls. Powell and his men witnessed a river of rainwater cascading down the cliffs to join the Colorado, carving new landscapes and depositing new hazards in the river channel below.

The river today is significantly less treacherous than the river Powell knew. People have tamed the floods with dams and accounted for every inch of water consumption. But these developments on the river and the cities and industries that flourish beside it have introduced a new danger. People have gained control of the river, but in exchange they have become utterly dependent upon it, putting themselves in a new position of peril.

The Grand Cañon at the foot of the Toroweap – Looking East.

Engraving by William Henry Holmes, 1882.

Before Powell

Centuries before Powell explored the Colorado River, another civilization had developed and flourished for well over a thousand years before their reliance on the Salt River, a tributary of the Colorado, left them susceptible to an extended drought. It took about three generations for this civilization to collapse in 1450 A.D. Their descendants call them the Hohokam , meaning “all used up.”

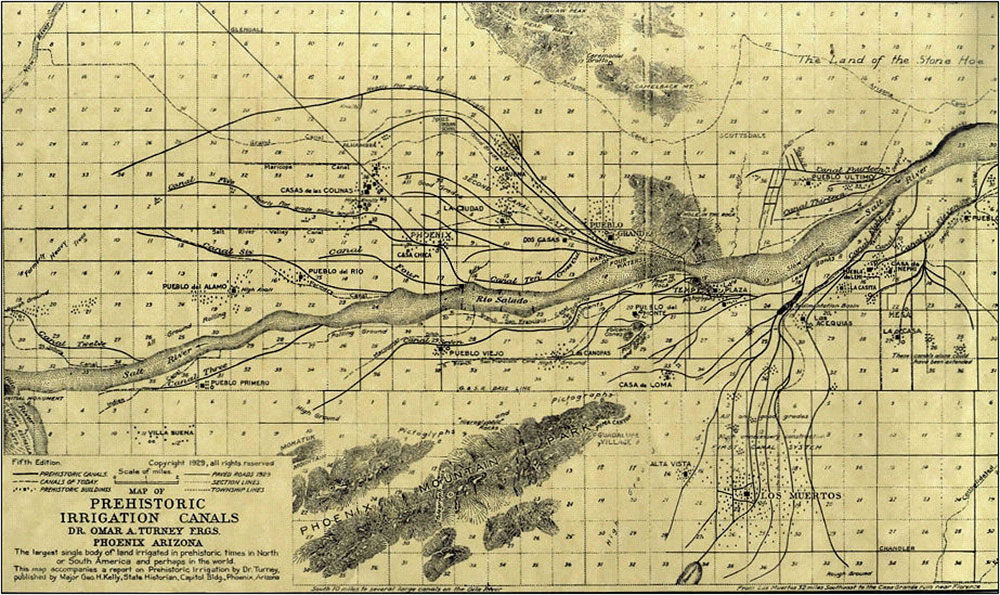

The Hohokam left an extensive footprint on the landscape. Archaeologists estimate that at its peak, the Hohokam irrigated 110,000 acres to feed about 60,000 to 80,000 people. They farmed squash, beans, corn and agave and ate the jackrabbits they found nibbling vegetables in their fields.

Archeologists used to believe the Hohokam accommodated an increasing population by incrementally adding onto their canals. They now know differently. The Hohokam had to calculate the whole system before they built it. They had to know how much water would enter the system and gauge how the water would be distributed through miles of irrigation canals. Building and using these canals required complex math.

The Hohokam did not pump water to their fields; they let gravity pull the water through the system that branched from large trunk canals to smaller channels that deposited water into the fields. Hohokam canals are precisely graded earthworks took years of hard labor to build. They designed their canals so the water would flow at a consistent speed. If they made their canals too steep, the water would dig out the channel. If canals were too level, sediment in the slow water would clog the channel.

Map of Hohokam Irrigation Canals.

Drawn by Omar Turney, 1929.

The Hohokam’s canals lose about one to two feet of elevation for each mile of canal, a feat that is hard to accomplish even with today’s precision surveying equipment. The canals had to be maintained, too. Every year, people worked together to clear weeds and seal the walls with clay to prevent water seeping out.

Building canals is more than hard work; it is cooperation.

“People don’t organize and build canal systems through kinship; they do it through putting in labor, knowing they’re going to get a return of land and water,” said Jerry Howard, curator of anthropology at the Arizona Museum of Natural History and an expert on the Hohokam.

Howard says younger generations of Hohokam would branch out from their parents’ land by building their own irrigation community. Anthropologists find it significant that the older, established communities provided the builders of new irrigation communities with food during the years of construction, indicating a complex societal organization.

“Conflict resolution is a big thing in irrigation. Irrigation farmers always squabble.”

The ways people construct their infrastructure can be a solid indicator about the ways their society is structured, Howard says. He believes a decision-making body presided over the irrigation communities, each of which could be as large as 27,000 acres, and resolved water use questions concerning canal building, maintenance and water allocation. “Conflict resolution is a big thing in irrigation,” he says. “Irrigation farmers always squabble.”

Howard is attempting to use clues left by these ancient societies to determine any parallels to the modern ways humans manage limited water resources. His investigations into whether the water belonged to communities or was allocated by a dominant political body paralleled what John Wesley Powell argued centuries after the Hohokam civilization collapsed.

Around 1,000 A.D., the Hohokam seemed to have reached the physical limits of the Salt River in central Arizona. Archeologists say Hohokam remains from that time show signs of severe malnourishment and suggest that for 450 years prior to their disappearance, the Hohokam merely eked out a living.

“When people drop out of the archeological record and we can’t see them anymore in the ground, it’s hard to know what’s going on,” says Howard. To form hypotheses about what happened to the Hohokam, he has looked at modern irrigation societies for characteristics they have in common.

Two Influential Groups

Powell’s first expedition to the West in 1869 made him a national hero. He successfully appealed to Congress for funding for a second trip, which would lead him to encounters with Mormons, as well as Ute, Hopi and Shivwits tribes, groups who had all adapted to thrive in the desert.

Only miles from where John Wesley Powell was born in Mount Morris, N.Y., Joseph Smith founded a religion that would profoundly affect the history of the Western landscape. Mormons had been persecuted in the East and settled on the meager lands in Utah Territory around 1847. They learned quickly how to subsist and thrive in the desert by mastering irrigated agriculture.

As a group, Mormons had several advantages. They believed that their great faith that God had given them the desert and the ability to live there. The hierarchical structure of their society unified members completely around the church.

“It freed the communities from individuals squabbling over water rights. It allowed the amassing of capital to undertake new projects and provided a cushion of security when projects failed,” says Donald Worster, in his book Rivers of Empire . Worster is the author of multiple histories on Powell and on Western development.

Just as it had with the Hohokam, the desert demanded the Mormons work communally. This emphasis on organization helped the church leaders consolidate power and assert that the water belonged to everyone, not individuals.

“That notion, a radical one by the standards of mid-nineteenth century America, was justified by the argument that in such an arid place, where water was scarce and survival easily put at risk, a single authority must have ultimate jurisdiction over its disposal,” Worster writes.

The communal concept enriched the settlers and the church, which was funded by its people’s mandatory offerings. Mormons’ social structure demonstrated certain characteristics—community cooperation, strong leadership and reliance on scientific knowledge—that John Wesley Powell would one day recommend Congress adopt as guidelines in settling the West.

“He was interested in how this society that had existed for 900 years had been able to survive and develop agriculture based on almost no water.”

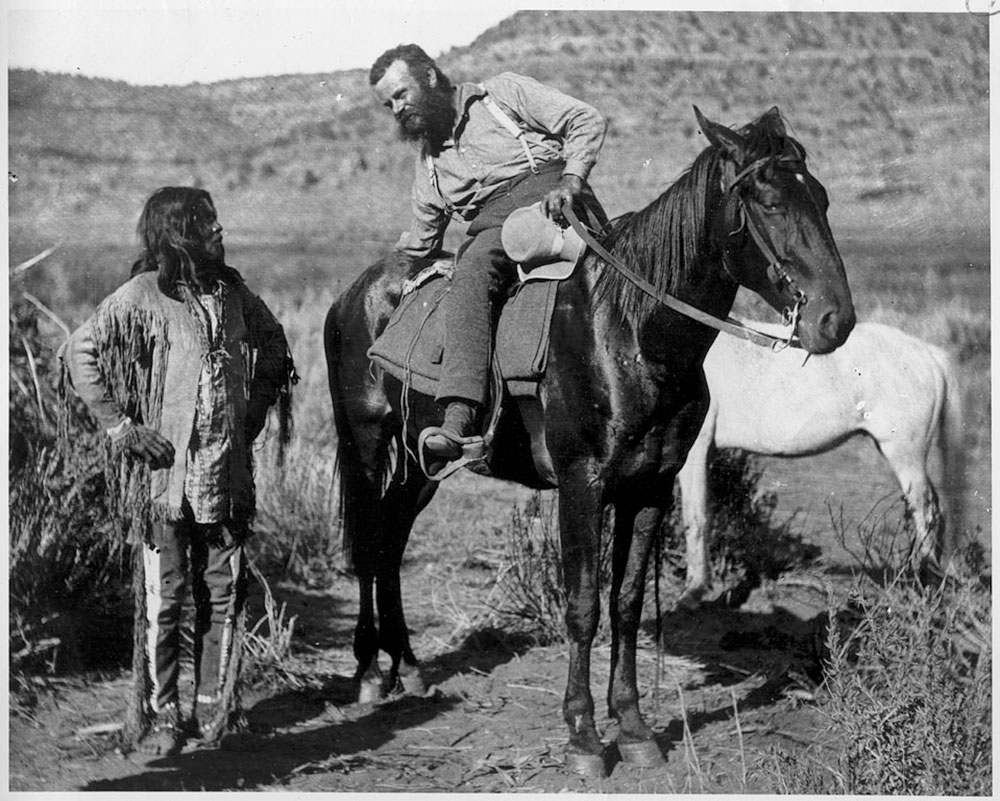

Powell also spent time with numerous Native American tribes during his second expedition. “He was interested in how this society that had existed for 900 years had been able to survive and develop agriculture based on almost no water,” Mark Law, historian and board of directors president of the Powell Museum , said of Powell’s time with the Hopi. “They showed him how they made little catchment basins and how they made irrigation ditches. All of this, Powell absorbed like a sponge.”

Powell learned from the Hopi ways to make a viable living in the desert and that water should be collected and spent judiciously.

John Wesley Powell and a member of the Paiute tribe.

Photo by John K.Hillers, 1871-1874. Smithsonian Institution.

Simple Logic

In his writings, Powell indicated how spending time with Native American tribes and Mormons influenced his ideas. He believed that cooperation at the community level, with respect to water use, held the key to successfully settling the West.

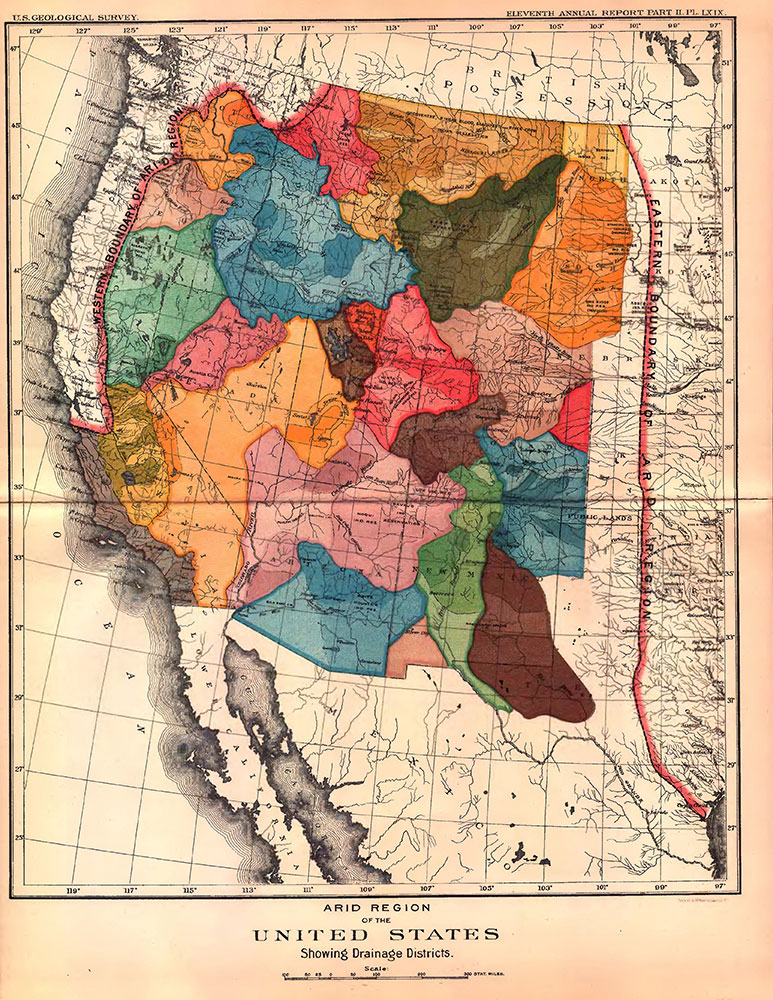

In 1878, he submitted to Congress his Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States. In his report Powell emphasized the importance of organizing political bodies around watersheds, which he defined as “that area of land, a bounded hydrologic system, within which all living things are inextricably linked by their common water course and where, as humans settled, simple logic demanded that they become part of a community.”

Powell did not oppose development in the West. But he questioned repeatedly who would control the scarce water so crucial to any settlement. “It was his vision of how this technological civilization built on water control was to be governed that differed [from the power elite of his time],” writes Worster. “Was it to be run by capitalists or by the people?”

Powell proposed that because water was so fundamental to the future of the West, political borders should be drawn according to the region’s water resources rather than along imaginary meridians.

Powell was emphatic that the West represented a chance for the American people to control their resources and destiny. Powell proposed that because water was so fundamental to the future of the West, political borders should be drawn according to the region’s water resources rather than along imaginary meridians. He even drew a map famous for proposing states’ borders along the lines of watersheds.

“These new units, not states or territories, would resolve issues of water sources in rivers flowing across political boundaries,” says a section on Powell in a history of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Powell suggested that the government grant people large tracts of land on which they would be encouraged to form and control small communities, herding or grazing cows or sheep. These communities would subsistence farm with the help of small dams or diversions. Congress, however, resisted these notions of restricted development.

In the same way that blank spots on a map called out to the explorer, the undeveloped areas on the newly complete map of the United States motivated politicians.

“Western water and land interests were fearful that Powell and his ideas would place a moratorium on Western development.”

“Western water and land interests were fearful that Powell and his ideas would place a moratorium on Western development and reverse a century-long policy of the disposal of the public lands,” explains the history of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

As private money gained a foothold in development rather than the small, water-minded communities Powell supported, a severe drought in the 1890s caused the ruination of settlers who had attempted individual irrigation projects rather than follow the model of success set by the Mormons and Native Americans. Simultaneously, an economic downturn suppressed some of the private money that had buoyed development until then.

“[The farmers and developers] were forced to admit that in order to sustain their population advance in the face of an adverse climate, they needed irrigation – and on a big scale,” writes Worster.

Persevering through these less than ideal conditions rather than relenting to nature, farmers and developers convened in Los Angeles at the second annual International Irrigation Congress. In August 1893, they gathered to rally their cause, galvanize their following, and appeal to the federal government for support.

They needed governmental support to fund the large water projects they believed would sustain the expansion they envisioned. There, Powell told the assembled hopeful simply, “You are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights for there is not sufficient water to supply the land.”

But no one listened.

Rising from the Ashes

Powell’s explorations had culminated in a clear message: Populations in the West should not become dependent on the region’s limited water resources to sustain large, permanent communities.

Centuries before Powell’s journey, the Hohokam’s abrupt collapse had proven this thesis to be true. Since Powell’s explorations and predictions, people have come to realize the truth of his forecasts that concentrated development leads to water dependence and vulnerability.

In 1868, more than 400 years after the Hohokam disappeared from the archaeological record and a year before Powell’s first expedition down the Colorado, a man named Jack Swilling had come across some ditches in the Arizona desert . They were ancient Hohokam irrigation canals. With a little work, he and some others excavated them and once more used them to divert water to irrigate land, on which they grew hay to feed government horses. Sensing economic opportunity, others soon joined them, and a small settlement formed on the banks of the Salt River, a tributary of the Colorado. In 1870, the population numbered 235 people, and by 1900, the county recorded 20,457.

The roughneck founding fathers had squabbled briefly over what to name their growing village. Swilling , a Civil War veteran, favored calling it Stonewall, after the Confederate general. Another man suggested something more classical.

They should call it Phoenix.

That once dusty settlement is today a city of 1.5 million people who depend heavily on the Colorado River and its tributaries for water. Powell, the visionary, would not be surprised.

Powell’s Map proposing political units be organized by watershed.

U.S. Geological Survey.

Sources:

Arizona Museum of Natural History. (2013). The Hohokam. Retrieved July 2, 2013, from http://www.azmnh.org/arch/hohokam.aspx

City of Phoenix. (2013). Out of the Ashes. Retrieved July 2, 2013 from http://phoenix.gov/citygovernment/facts/history/

City of Phoenix. (2013). Your Water. Retrieved July 02 2013, from http://phoenix.gov/citygovernment/facts/history/

Dolnick, E. (2001). Down the Great Unknown: John Wesley Powell’s 1869 Journey of Discovery and Tragedy through the Grand Canyon. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers.

Fagan, B. (2011, March/April). Phoenix’s looming water crisis. Archaeology, 64(2), Retrieved from http://archive.archaeology.org/1103/insider/phoenix_water_crisis_hohokam.html

Howard, J. Hohokam Legacy: Desert Canals: (Pueble Grande Museum Profiles No. 12). Retrieved July 02, 2013, from http://www.waterhistory.org/histories/hohokam2/hohokam2.pdf

Hyland, A. (2001, September 12). 16 Things: KU history professor, environmental historian recounts personal history. Lawrence Journal-World.

National Public Radio. (2013). The Vision of John Wesley Powell. Retreived July 02, 2013, from http://www.npr.org/programs/atc/features/2003/aug/water/part1.html

Powell Museum. (2012). Retrieved July 2, 2013, from http://www.powellmuseum.org/index.php

Powell, J. U.S. Department of the Interior, (1879). Report on the lands of the arid region of the united states, with a more detailed account of the lands of utah. Retrieved from Internet Archive: http://archive.org/details/reportonlandsofa00geog

Powell, J., Cooley, J., & Others. (1988). Exploring the Colorado River: Firsthand Accounts by Powell and His Crew. Mineolo, NY: Cover Publications, Inc.

U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. (1889). Eleventh annual report of the u. s. geological survey, ,1889-1890. part II. Irrigation.. Retrieved from website: http://www.aqueousadvisors.com/powellmap.pdf

United States Census Bureau (2013, June 27). Phoenix (city), Arizona. Retrieved July 2, 2013 from, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/04/0455000.html

Worster, D. (1985). Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West. New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Worster, D. (2001). A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hillers, J. K. (Photographer). (1873). John Wesley Powell & Native American [Print Photo]. Retrieved from http://www.fotosimagenes.org/hohokam

Holmes, W. H. (Artist). (1882). The Grand Cañon at the foot of the Toroweap – Looking East. [Print Drawing]. Retrieved from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grand_Canyon_at_the_foot_of_the_Toroweap_-_looking_east,_William_Henry_Holmes.png

Pitz, H. (Artist). (1939). Major Powell Descends the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, 1869 [Painting]. Retrieved from http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artwork/?id=19749

Turney, O. A. (Photographer). (1929). Map of prehistoric irrigation canals [Print Map]. Retrieved from http://www.fotosimagenes.org/hohokam