What Happens When You Go Against the Flow

By HANNAH WEINBERGER

One does not really conquer a place like this. One inhabits it like an occupying army and makes, at best, an uneasy truce with it.”

– Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert

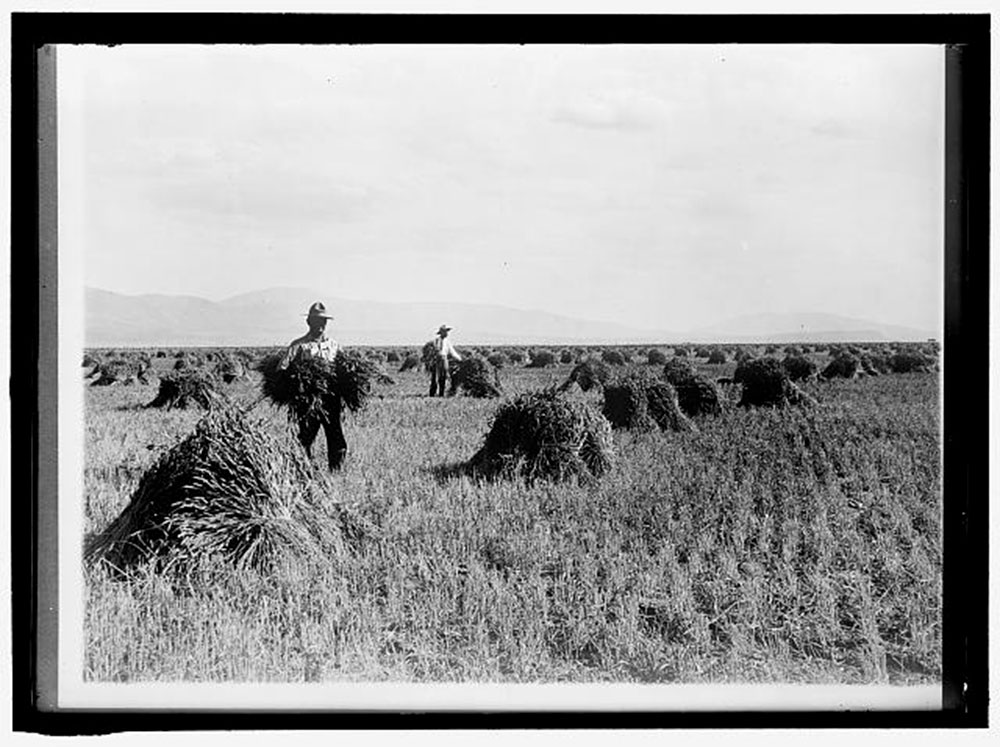

Minidoka Project. Photo by Harris & Ewing. Courtesy Library of Congress.

MINIDOKA IRRIGATION PROJECT, IDAHO, 1960s. Robert King, bundled in flannels and wearing thick boots, pulls a cumbersome siphon from the ditch that divides his family’s 200-acre farm. He maneuvers the siphon to a furrow in the soil, sprinkled with budding wheat, alfalfa and potatoes. The wind picks up, hurling dust and water everywhere. If it were warmer, he thinks, he wouldn’t mind getting wet.

Shielding his eyes and shivering as spring chill whips about him, King can just make out where the ditch tumbles over a nearby hill. Beyond it, Minidoka Dam holds back the farm’s lifeblood in Walcott Lake; without the lake and the sinuous Snake River that feeds it, thirsty crops wouldn’t stand a chance.

The opportunity to care for this land came twelve years earlier when his father, Vern King, returned to Idaho from combat in Korea. He wrested an opportunity to start fresh by entering a Bureau of Reclamation lottery to win land in the Minidoka Irrigation Project, the million-acre expanse where he had grown up working on his father’s farm.

“All the local veterans put in for it, and he was the only one who was drawn,” King says proudly.

Foregoing an engineering degree at Michigan State University, Vern King brought his wife and then 1-year-old son Robert nine miles down the road from his grandfather’s farm to start his own. If Vern could irrigate unruly volcanic dirt successfully within a few years — with the help of government-built waterways — he could keep it.

Nearly 60 years later, the farm still operates with the younger King’s cousin at the helm. It hasn’t been easy, King says, but for the families who figured out the land, it was worth it — just as settlers moving west had learned as early as the mid-1800s.

Congress supported agriculture to encourage Western settlement, King notes. “They generated the opportunity for farmers in the West to generate revenue.” Irrigation, he adds, “allows us to have the kind of country that we have today.”

Today, people still flock west. Irrigation supports more than 40 million people in the Colorado River Basin’s 246,000 square miles of riverbed, farmland and cities in some of the driest states in the country. When presented with a map of the region, some wonder why the largest populations of Americans using the Colorado are nowhere near it. They wonder why 5.5 million acres of irrigated land and cities far away on the Pacific Coast even developed at all. How is it possible that these cities are still growing when the river and animals that rely on it are under duress, so much so that the Colorado River was named 2013’s most endangered river in the country?

“The river is in the emergency room. It’s got tubes in it, and it’s being monitored, and it’s about to die. But we don’t want it to happen, so we just put more machines into it.”

“People seem to think that we delight in destroying the environment,” says King, speaking as an interstate water policymaker in Utah who irrigates on a much grander scale than a Minidoka farm. King works with people from each basin state to create strategies in operating dams along the Colorado. It’s not his job to tell people how to use their water, he says, but to make sure water managers take only their designated shares of it. Today the river is managed based on “a series of tradeoffs made in the past,” he notes.

“We’re still trying to minimize the environmental impact with what’s already there and what’s already developed,” he says, but dams “are an integral function of being able to live in the West.”

Historically, civilizations rose along the banks of freshwater sources, with bodies of water defining city-planning schemes. But cities using the Colorado River couldn’t be restricted to and defined by a river. Instead, they sought to define it, and tug silty flows throughout the Southwest to make the desert bloom. Keeping the river healthy, observers say, hasn’t always been a priority.

Historians and activists argue that the river’s current shape and the way Westerners have and do use it reflects a century of short-term solutions to problems that needed long-term ones.

“The river is in the emergency room,” says John Weisheit, conservation director at non-profit agency Living Rivers. “It’s got tubes in it, and it’s being monitored, and it’s about to die. But we don’t want it to happen, so we just put more machines into it.”

Establishing Claims

When President Thomas Jefferson bought 800,000 square miles of land from Napoleon in 1803 for $15 million, he did so in part as a protectionist measure.

“One of the lessons of the settling of North America by European nations was that, to hold onto land, you needed to settle the land,” says water expert Douglas Kenney. “Ensuring settlement became a high national security objective.”

Fearing a possible French empire in North America (and lingering Spanish and British aspirations), Jefferson jumped to claim the region first and then see what it was worth. However, his proactive measures set a precedent for American motivations that influenced resource use: take it before someone else can.

With vulnerable country and little direction as to what to do with it, Jefferson deployed Army volunteers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the West under the pretext of monopolizing fur trading with natives before the British could.

Lewis and Clark’s evaluations were inconclusive, but many contemporaries’ appraisals of the land were clear-cut. Explorer Zebulon Pike said that Americans should “leave the prairies incapable of cultivation to the wandering and uncivilized.” The reaction to Lewis and Clark’s reports confirmed as much; their reports resonated with fur-trapping mountain men looking for beavers, wealth and adventure. They descended upon the region, collecting pelts in droves. Beaver populations, like many western resources, soon dwindled.

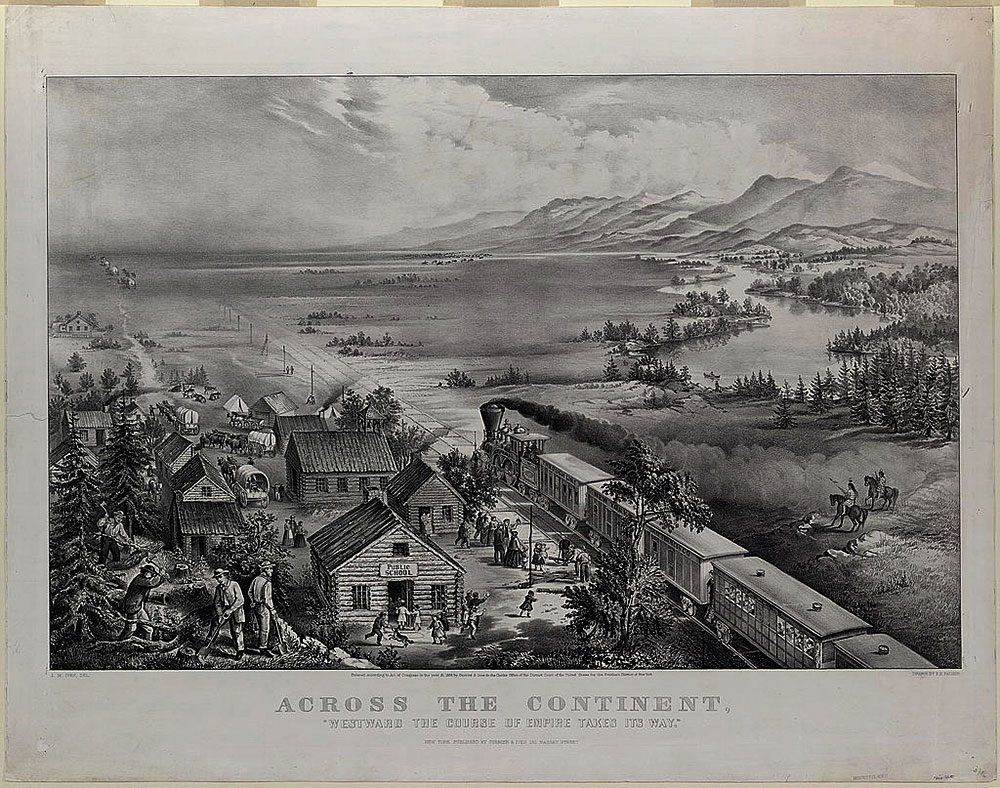

After the War of 1812 substantially delayed British conquest in North America, Americans weren’t so much concerned with taking things first but in claiming what they considered rightfully theirs. Gov. William Gilpin of the Colorado Territory was an early proponent of Manifest Destiny, the idea that Americans were meant to conquer the continent. He envisioned that ideal empire in his book, The Central Gold Region.

Although stunted, he wrote, the country could set the bar for empire by constructing a transcontinental railroad. America, situated between Asia and Europe amidst a wealth of raw material, would “lead the host of nations to a new order of civilization” by developing faster trade, reaping profits from that trade and reinvesting in industry.

Western senators, speculators and a burgeoning railroad industry agreed. A transcontinental railroad would reduce dependence on lengthy and costly maritime shipment of resources back East. States zigzagged with railroads would have greater chances of population growth and trade, extending not simply a U.S. flag but a very rich U.S. flag throughout the western territory.

The only threat to that civilization: the wild lands in between. To Gilpin, river basins and mountains unsuitable for trains had no value. They were obstacles to progress until they were subdued.

“The West was going to save the United States from inevitable decay. They were going to trade space for time.”

Decision makers “weren’t thinking ecologically,” says Mark Fiege, a professor of history at Colorado State University. “They were thinking in a powerful way, but it was deeply reductive and very authoritarian toward the environment and toward people.”

Early thinkers like Jefferson thought every civilization had a lifespan and that settling people in a new, undeveloped frontier with wealth potential could give America adrenaline.

“The West was going to save the United States from inevitable decay” or forestall it, Fiege says. “They were going to trade space for time.”

For development to happen, officials would need to do more than induce a few settlers into visiting the West. Under precedent of the Homestead Act of 1862, which gave settlers land in the Great Plains, politicians and businessmen set about devising how to induce a mass migration to western seaports and rivers close by. The West and its resources — gold, timber, coal, and the like — would be harvested and shaped to the will of the American people through small farming and land ownership.

Celebration of Westward Expansion. Drawing by F.F. Palmer. Lithograph by Currier & Ives. Courtesy Library of Congress.

A Shallow Appraisal: Jumping the Gun

At the first Irrigation Congress, held in Salt Lake City in 1893, scientist and explorer Major John Wesley Powell beseeched irrigation boosters to take a step back and look closely at the Colorado River basin’s capacity. He had rafted and assessed the river’s length and felt a need to burst their empire-focused bubble. Big players in the irrigation movement bridled as Powell laid out the facts:

But short-term political goals and greed made decision makers shortsighted. When economic depression hit in the 1890s, the need for immediate and sweeping solutions obscured honest recognition of what the West’s limited water resources could handle. Settlers must move West not only to improve America’s chance at continental empire, said ‘Gilpinites’ who followed the principle of Manifest Destiny, but also to develop resources and build back the nation from depression and the Civil War as soon as possible. Somehow, the land would be irrigated.

In 1902, a handful of western senators interested in mobilizing promising raw materials in their states and increasing their populations finally found a friend in then-President Theodore Roosevelt. He authorized the creation of a new federal agency, the Reclamation Service, and put it to work manipulating western rivers toward settlers’ farms. Irrigation projects would be funded through sale of public lands.

At the same time, Roosevelt authorized the Newlands Act named for Sen. Francis Newlands of Nevada, allowing farmers to keep land if they irrigated it with water from federal irrigation projects. The independently wealthy Newlands had attempted large-scale irrigation projects on his own but failed for lack of funding; he realized that only a budget as large as that of Congress’ would enable his dream.

To rationally go about changing the landscape and persuading settlers to move west, irrigation boosters had to find evidence refuting Powell’s argument about the river basin’s limitations. An alterative notion explained briefly as “rain follows the plow” answered this need. No matter how arid the land, the idea held, farming would make the air around it more humid; tilling dirt exposed loamy earth that could better retain rain. Although the region usually did not get much rain, a climatic blip about that time made the West slightly wetter than usual, and the notion gained steam. With fervor stirred for land reclamation, people moved to the West.

“I think they oversold it,” King says. “People didn’t realize how much hard work it would be.”

King, whose first memory is being on a tractor at age 5, didn’t know anything but the farm until he was 20 years old. Today, he realizes how difficult working the land really was. Even farmers in the more modern-day Minidoka Project weren’t prepared to spend three years clearing sagebrush and rocks that hurt farm equipment and irrigating before their plots could go into full production. Unlike King, who was trained to work the land by both his father and grandfather, most settlers found they hadn’t been so clear on what to do with land they’d been hasty to nab.

“Many projects thus wound up where they were bound to fail, though no one told the homesteaders.”

“It was dry and hot and windy, which are all things that are not as common back east,” King says. “It’s pretty bleak compared to say Illinois and Ohio where it’s green and lush.”

Simply moving West proved not to be a farming cure-all. Many didn’t know how to irrigate arid land, let alone any land. The ones who stuck with it couldn’t grow enough in the dry dirt to pay back their loans — most of the projects had been built where politicians wanted them, rather than where surveyors said they should be.

“Many projects thus wound up where they were bound to fail,” James Powell writes in Dead Pool, his examination of reclamation, “though no one told the homesteaders.”

After two decades of reclamation, only 11 percent of loans had been repaid. A report released in 1924 revealed the Reclamation Service’s lack of oversight. Approximately 95 percent of the landowners receiving money for irrigation never actually irrigated their land. Somehow, projects had been built on private lands instead of the public ones whose sale would pay for dam construction. Congress gave prime public lands away for mining and railways, allowing railroad companies to create monopolies on plots nearest their tracks and to hike shipping costs to farmers. Many farmers quickly gave up, and the majority of those who didn’t could grow only cheap surplus crops like alfalfa and wheat, not earning enough to pay for use of water. The more loan defaults threatened, the more the Reclamation Service extended the loan period — to the point where many farmers would die before repaying their loans. Some sold land to speculators. All the while, Congressmen looking to serve more voters and boost economies asking to build projects in their states, too.

“The sponsors of Federal reclamation believed it would be a simple matter to change arid, unimproved land into farms,” the study authors wrote. “Time has shown that this was a mistake. It is beginning to be realized that [irrigation] development requires a study of agricultural and economic problems, and the working out of settlement and development plans if the land is to be brought under cultivation without disastrous delays and waste of money and efforts.”

By the time the study appeared, small farmers weren’t the Reclamation Service’s focus. As often happens after scandals, the Reclamation Service rebranded and changed its structure. It became the Bureau of Reclamation, an office under the direction of the Department of the Interior. It also began focusing mostly on the demographics that could support more exciting and lucrative projects; Congressmen, looking to serve more voters and boost economies, were asking to build in their states, too.

Shifting Priorities

The will to wrestle and overcome the environment came to a head with Southern Californians between 1900 and 1920. Residents of the newly rebranded Imperial Valley found themselves with a farming Mecca on their hands, save for the lack of a stable water supply. They hoped to farm the land between the Colorado and the bed of what had once been the Alamo River.

In 1900, engineers from a private company redirected Colorado River water into the Alamo successfully but hastily; 700 miles of canals made 75,000 acres fit for farming, but the canals kept clogging with silt. As a solution, they cut a new canal across the border in Mexico. It started filling before the Mexican government approved it.

Construction of Hoover Dam. Painting by William Gropper. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Lead engineer C.R. Rockwood accidentally helped reawakened not only the Alamo River but also a bygone inland lake named the Salton Sea. When the Colorado flooded in 1905, the river plunged into the Salton Trough — a sink big enough to hold more than half its annual flow – and destroyed 330,000 acres of crops, rendering the farmland permanently unworkable. A new canal – one that didn’t go through Mexico, to avoid any water conflicts – would be necessary.

Two hours west, Los Angeles was insatiably thirsty. Its population grew exponentially in the wake of two gold rushes, as did its value: It lay at the crux of bustling seaports, farmlands and railways, key ingredients for trade. William Mulholland, superintendent of the city’s Department of Water and Power, had nabbed the northern Owens River out from under small farmers through water rights purchases and the support of wealthy agriculture tycoons in the San Fernando Valley. But even the Los Angeles Aqueduct couldn’t supply the needs of both city folk and farmers.

The Bureau of Reclamation had been busy with smaller projects during World War I, but by its end, Powell’s nephew Arthur Powell Davis was in charge. Powell Davis believed that only a dam could sustain cities in need of drinking water and put down the floods that threatened farms. What’s more, because the river plunges 12,000 feet over the course of its 1,440-mile journey from La Poudre Pass Lake in Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico, the Colorado made dam hydropower effective and canals efficient. The residents of the Imperial Valley and Los Angeles were willing to lobby for the necessary waterworks: two channels and a flood-curbing dam.

“The Reclamation Service sees the handwriting on the wall,” professor Fiege says. “They recognized that rural people are running into trouble, and they realized that if you want to have a political power base, you’ve got to look to where the population is, and that’s the cities.”

As early as 1900, author William Smythe did, too. Calling the rich soil along the Colorado’s banks a “gift of the river” for the purpose of American prosperity, he noted the significance of controlling water.

“What is the key that will unlock the door to modern enterprise and human genius? It is the Rio Colorado,” he wrote. “Whoever shall control the right to divert these turbid waters will be the master of this empire.”

Black Canyon, along the border of Arizona and Nevada, was chosen as the site of the Hoover Dam. The Colorado River Aqueduct’s 242 miles of siphons, pumps and canals would extend 242 miles from Lake Havasu in Arizona to Los Angeles; eighty miles of canals would bring water from the Imperial Dam to the Imperial Valley.

“Water is the critical thing lacking to have a wonderful life.”

The Hoover Dam became a source of pride for the Bureau of Reclamation and Congress. Curved and massive, the concrete arch-gravity dam would soar more than 700 feet into the air, catapulting into record books. The dam squats mightily downstream of Lake Mead, a reservoir deep enough to capture 28.5 million acre-feet — 9.2 million gallons, or four times what Wisconsin uses annually. Today, the dam’s 19 generators produce enough energy to power 1.75 million average American homes. Hoover’s hydropower also could fund its construction; with the last generator’s installation, it became the most powerful hydropower facility in the world. Building the dam cost $49 million and more than 100 deaths throughout construction.

While the main pretense of the dam was to protect against floods, the reservoir would provide the two things that make societies flourish: power and dependable water.

“Water is the critical thing lacking to have a wonderful life,” Dead Pool author Powell adds. “If you put yourself in the mindset of the people in the ‘20s and ‘30s I mean, we’d all build Hoover Dam if we could.”

A boon to the New Deal agenda, dam building employed hundreds of jobless young men. Dams later provided electricity critical in developing military vehicles, artillery and the like.

In the end, the benefits of dams compounded by a drive to subvert the river’s power for electricity or other uses made damming the Colorado River an obvious choice to residents and legislators. But prospects of big dams made basin state officials worry about future access to the river, leading the way for a series of heated negotiations.

Dividing the Spoils

While measures were being put in place to give California its canals, the Supreme Court handed down a ruling that upended traditional western water use and solidified the importance of getting to western resources first.

Traditionally, anyone who owned land on a river could use the water flowing through it, a notion known as riparian (or “river bank”) law. However, the court’s 1922 ruling in Wyoming v. Colorado replaced that doctrine with a new view on water use known as prior appropriation, briefly defined as “first in time, first in right.” No matter who owned land along a riverbank, the first people ever to have used the water had first dibs annually. That change established a premise for water use still observed throughout the basin today.

Prior appropriation “has everything to do with the mess that we’re in today,” says National Geographic contributer Jonathan Waterman. “In fact, whenever you get a good idea for conservation, you then have to address the prior appropriations doctrine and figure out ways around it.”

“To change water use, you’d have to get new losers to get new winners. It’s a finite resource. Somebody has to lose their water.”

The ruling worried officials in the six other basin states. California had used the river first decades before, and its thirsty population wanted to fund the pricey waterworks. With a head start of being “first in right,” California could drain the river before other states claimed their share.

Representatives from the seven states crammed into a Santa Fe lodge in 1922, hoping to set up a system for sharing the river before Congress approved the dam and channels. Then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover led the commission that came out with the Colorado River Compact, the first part of a doctrine known as the Law of The River, just in time.

“In hindsight, it’s easy to see lots of drawbacks depending on what your value set is,” King says of the Compact. “I think they did a good job, but there wasn’t a consensus. There was political horse trading, both in Congress and within the states, and acknowledgement that there would be impacts.”

Apart from dividing river water, the commissioners decided how the water should be used. The Compact’s first article lists proper uses, or beneficial uses of the water, for industry, home use, energy and above all agriculture. A goal of protecting the river wasn’t considered.

“At that time, conservation meant holding water in reservoirs for use during dry periods, which is a bit different than how we think of conservation now,” King says.

The states couldn’t agree on how to divide the water by states, even after six years of negotiations, so Hoover and commissioner Delph Carpenter scrapped determining distributions to individual states. Instead, they decided to split the states into an Upper and Lower Basin, divided at Lee’s Ferry, Ariz. Each basin would get slightly less than half the river’s annual, leaving buffer room in case of drought, or if Mexico wanted in on the deal.

“(The) proposal thus solved one problem only to create another” by delaying state appropriations, Powell writes in Dead Pool, “but it did allow the commissioners to show that they had accomplished something.”

Each basin was given 7.5 million acre-feet of water, about a quarter of what Lake Mead could hold, and what the commissioners believed to be slightly less than half of one year’s average annual flow, leaving a buffer in the event of drought. The Lower Basin — including California — had primary water rights. However, the data they used were incomplete. The commission expected 18.5 million acre-feet to be available each year, overestimating by about 3.5 million acre-feet. The commission had only 20 years of thorough stream flow records, and it would be decades before they found out that those were the wettest years the basin had seen in centuries. The supposed buffer was entirely imaginary.

In addition to assuming that water flows had been normal for the prior few decades, the commissioners made another assumption when the Compact was ratified as part of the Boulder Canyon Project Act in 1928. In the Act, Congress approved $165 million for construction of the dam at Boulder Canyon and the All-American Canal to the Imperial Valley; put the Secretary of the Interior in charge of the Lower Basin; and then divided how much water would go to the Lower Basin states when the states’ representatives couldn’t decide how to do it themselves. The Californian majority gained the most and more than any other state. More than that, Californians won the right to use any water the other states failed to use, setting Californians up for decades of feeling like they had more water than they really did.

More resources put canal-backing California in a position to maintain its population growth and political power, professor Fiege says.

“Most people think that everything pertaining to a state begins and ends at the boundary of a state,” he says, “but California commands an enormous amount of power.”

Despite giving California special consideration, the commissioners went ahead without Arizona’s consent in their haste to agree, precipitating three decades of infighting.

Consideration for key players — Mexicans and Native Americans — was minimal. Should Mexico ever want water, the commissioners wrote, the supplies would have to come from surplus. The river’s health was never explicitly considered.

Today, distribution of populations throughout the Southwest is quite different than in 1928, and the Compact’s flaws have become apparent. Water administrators, such as King, find themselves considering the Compact with a lawyer’s meticulousness to provide for their constituents.

“We kind of have adjusted the interpretation, not adjusted the Compact,” King says. “The first rule of the Law of The River is whatever the seven basin states and the federal government can agree to can probably be worked into the Compact.”

Some people would like to scrap the system altogether and start fresh, King says, but doing so would be reckless. Agreements like the Compact have a lot riding on them.

With something “that impacts this many people, that has infrastructure built upon it, you just can’t go in and change things overnight,” he says. “Otherwise, you’d end up with some pretty drastic consequences.

“To change water use, you’d have to get new losers to get new winners,” he says. “It’s a finite resource. Somebody has to lose their water.”

Sources:

A Million A Month: Man Who Will Spend That Sum For the Government. (1097, April 8). The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/537353699/13EE70BE59A6F4F755A/3?accountid=14244

Behm, D. (2013, February 23). Wisconsin uses over 2 trillion gallons of water a year. Milwaukee-Wisconsin Journal Sentinel. Retrieved from http://www.jsonline.com/news/wisconsin/wisconsin-uses-over-2-trillion-gallons-of-water-a-year-4q8p3fb-192763861.html

Fatalities at Hoover Dam. Retrieved from http://www.usbr.gov/lc/hooverdam/History/essays/fatal.html

Gibbard, F. (2005). Wyoming v. Colorado: A “Watershed” Decision. The Colorado Lawyer, 34(3), 37. Retrieved from http://www.cobar.org/tcl/tcl_articles.cfm?articleid=4063

Gilpin, W. (1860). The Central Gold Region, The Greain, Pastoral, and Gold Regions of North America with some New Views of its Physical Geography; and Observations on the Pacific Railroad. St. Louis, MO: Sower, Barnes & CO.

Harrison, J. (2008). Lewis and Clark. Northwest Power and Conservation Council. Retrieved from http://www.nwcouncil.org/history/LewisAndClark

Hoover Dam. (1931, March 8). The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/150304517/13EDC92C5F26B1ECDC/13?accountid=14244

Hoover Dam and the Colorado River Compact, United States. Retrieved from http://blogs.umb.edu/buildingtheworld/energy/hoover-dam-and-colorado-river-compact-united-states/

Hoover Dam Frequently Asked Questions And Answers. (2009). Retrieved from http://www.usbr.gov/lc/hooverdam/faqs/powerfaq.html

Irrigation Battle Taken to Capital: Wyoming-Colorado Fight over North Platte Water To Be Settled in Washington. (1933, January 8). New York Times. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/100628936/13EDC9567CA34F6F913/3?accountid=14244

Langmead, D. (2009). Icons of American A333rchitecture. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=OTh8b2cyGBcC&lpg=PA213&dq=creation&pg=PA213#v=onepage&q=creation&f=false

Living Rivers. (2004, August 06). Colorado Riverkeeper. Retrieved July 02, 2013, from http://www.livingrivers.org/staff.cfm

Loeffler, J., Wescoat, J. (2013). Colorado River, Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2013, July 02 from, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/126494/Colorado-River

Making the Desert Bloom: The Rio Grande Project- Reading 1. (2012, March). Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/141RioGrande/141facts2.htm

McMillion, S. (2013). Watered Down: Can the mighty Colorado River reach the sea? The Nature Conservancy Magazine.

NIDIS Map and Data Viewer. Retrieved July 02, 2013, from http://gis.ncdc.noaa.gov/map/drought/US#app=cdo

Perkins, M. (2013, June 23). [Earth Talk: Overtaxed Colorado tops endangered rivers list]. AZ Daily Sun. Retrieved from http://azdailysun.com/lifestyles/columnists/earthtalk-overtaxed-colorado-tops-endangered-rivers-list/article_ce930b2b-c872-59b3-97f5-861902e3a1a3.html

Reconstructed Naturalized Colorado River Flow at Lees Ferry Near Page, Arizona [Web Graphic] (2009, February ). Retrieved from http://www.climas.arizona.edu/files/climas/images/feature-articles/feb2009_fig2.gif

Reisner, M. (1993). Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water, revised edition. Penguin. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=Akn6rUgR_eEC&pg=PT117&dq=fact

Riparianism. (1910, September 17). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/159464612/13EDC92C5F26B1ECDC/5?accountid=14244

Speers, L. C. (1927, February 13). Seven States Dispute Over Boulder Dam. New York Times. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/104228274/13EDC95B81D34F6F913/1?accountid=14244

Sunset. (Vol. 4-5, p. 293) (1900). Southern Pacific Company. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=-xu8grhp9T8C&pg=PA293&dq=

United States Department of the Interior. (2013, February 27). Glen Canyon Dam: Adaptive Management Program. Retrieved July 02, 2013, from http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/amwgbioALT_king.html

U.S. Congress, (1928). Boulder Canyon Project Act. Retrieved from website: http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/pdfiles/bcpact.pdf

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation. (2012). Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study, Reclamation Managing Water in the West, Retrieved from http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/programs/crbstudy/finalreport/Executive%20Summary/Executive_Summary_FINAL_Dec2012.pdf

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation. (1922). Colorado River Compact. Retrieved from website: http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/pdfiles/crcompct.pdf

United States General Accounting Office, Bureau of Reclamation. (1997). Reclamation Law and the Allocation of Construction Costs for Federal Water Projects. Retrieved from website: http://www.gao.gov/archive/1997/rc97150t.pdf

William Mulholland (1855-1935). Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/people/i_r/mulholland.htm